June 20, 2025

I was asked for book recommendations a few weeks ago, and a couple of heuristics for choosing books popped into my head. They surprised me a bit, so I thought I should write them down. Hence this blog post.

But first, a caveat. Any set of heuristics are secondary to the prime directive of reading, which is this:

The right book to read is the one you want to read.

Since prime directives are serious business, it comes with a note and an addendum.

The note addresses a common confusion that comes from not paying attention to small differences in language. It is this:

To want to read something is not the same as to want to have read something.

It is common to want to have read something. But in order to satisfy the prime directive, you must want to have read it so bad that it also makes you want to read it. Otherwise, it’s the wrong book, you won’t read it, and for good reason. It’s important to recognize this situation though, as the book you want to have read might be blocking the book you want to read.

The addendum addresses another gap between desires and reality. It is this:

The right book to read is the one you have the energy and the headspace to read.

Sometimes you truly want to read a certain book, but you’re not up to it. It will have to wait until you’re in a better place. That’s ok. There are many books worth reading. Again, beware of blocking.

With that out of the way, let’s look at my new-found heuristics. They apply to the situation where you don’t necessarily know which book you want to or have the energy to read, or there are multiple candidates. Also, the context is books that are relevant for people in their professional capacity as part of the software industry.

They’re all roughly the same heuristic, but not quite. I’ll walk through each in turn.

One reason to avoid reading bestsellers is that you don’t need to read them, since you’ll pick up the gist of them through osmosis. You don’t need to read “Team Topologies” by Skelton and Pais, simply because there’s no way to remain ignorant of it. If you’ve been a part of the software industry mainstream over the last five years, you’ll have a working understanding of what platform team is. You’ll know that the goal is to optimize for “fast flow”. You may have questions about exactly what that entails, but that’s ok. I also have questions, and I’ve actually read the book. (I said it was just a heuristic.)

Professor of literature, Pierre Bayard, describes the process of osmosis in the book “How to talk about books you haven’t read”. Many literary scholars have never read Hamlet or The Brothers Karamazov, but that doesn’t stop them from engaging in scholarly discussions. They know the plots well enough through years of exposure. It is a sort of professional bullshitting. Is it harmful? Bayard doesn’t seem think so.

Another reason to avoid bestsellers is that reading what everyone else is reading makes you predictable and boring. There’s an opportunity cost to reading a bestseller. You’re depriving yourself of the chance to learn something that not everyone else knows. The positive formulation of this heuristic is to read idiosyncratically. Seek out niches. It gives you different perspectives than your colleagues, and so gives you a greater chance to have something to contribute.

It’s better for you and for the groups you are part of if you read something that not everyone has read. It creates a bigger pool of collective influences. If everyone reads more broadly and varied, it allows for more fertile cross-pollination of ideas as well.

When will you want to override this heuristic and nevertheless read a bestseller? One reason might be that you start to suspect that no-one in your surroundings has actually read the book and that the bullshitting is getting out of hand. There’s a lot of talk, but also a lot of confusion and hand-waving. You might want to cut through that by going to the source and figuring out what, if anything, the book actually says. Of course you might find that reading the book doesn’t resolve the confusion, but then at least you know that.

We live in a pop culture. Both the technology world and the business world are ridden by fads. A lot of it is noise, with little lasting value. Spending our time reading only new books is risky. It exposes us to a lot of things that will be gone tomorrow. We may as well enlist the help of time, let it do some sorting for us. It’s not perfect, of course. Sometimes great books are largely forgotten too. In fact, since we live in a pop culture, pretty much all books are! But we can still find them, if we put in a little effort.

Note that I’m not saying “read classics only”. I have an ambivalent relationship with “classic” books on software. Lists of ostensible classics invariably contain a mixture of mediocre old bestsellers and canonicalized books that no-one has actually read. The archetypes are “Clean Code” by Robert C. Martin and “The Art of Computer Programming” by Donald Knuth, respectively. The former I can only assume makes the lists because it’s the only book many programmers have read, and the latter because it is imposing and has a cool name.

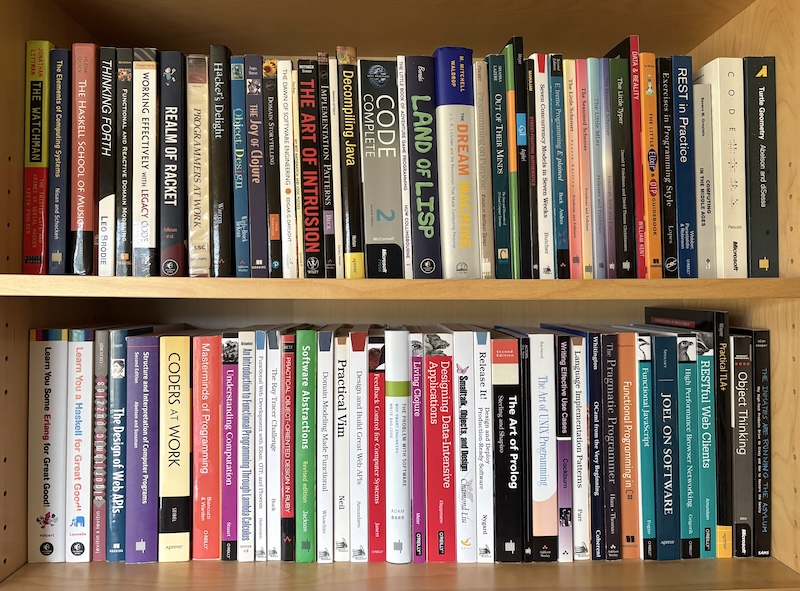

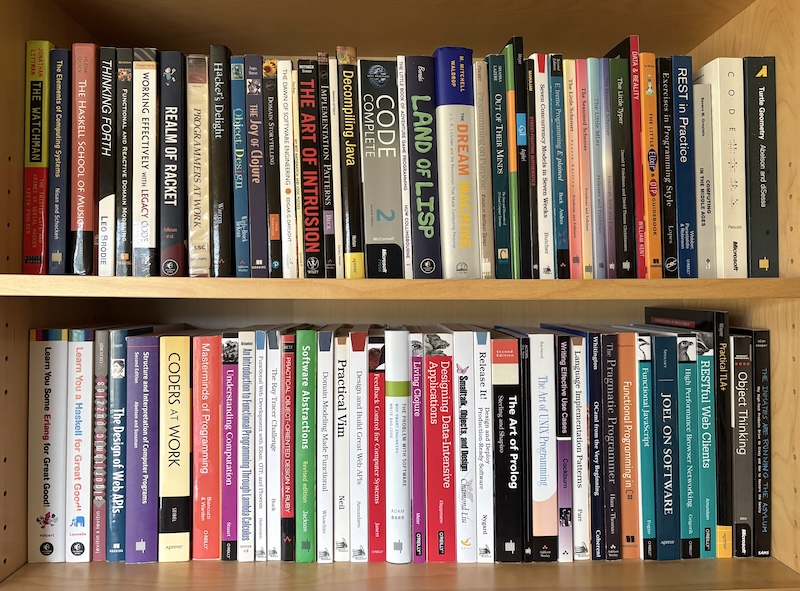

There are some genuinely good books on such lists as well, but they don’t need highlighting. Just Google it, and you will find all the permutations you want of the same list of ten books. I would rather like to point out that there are many other great old books that deserve our attention. A cult classic is “Thinking Forth” by Leo Brodie, which describes a language-and-domain-driven approach twenty years before the blue book by Eric Evans. And maybe design patterns would have fared better if people had read “Pattern of Software” by Richard Gabriel instead of “Design Patterns” by the Gang of Four? There are other, more obscure gems as well, like “Adventure in Prolog” by Dennis Merrit and “Mathematical Illustrations” by Bill Casselman. They’re great books, sitting on a shelf somewhere (or on a hard drive somewhere), waiting to be read, waiting to expand our minds.

It’s sad that we apparently aren’t aware of more than ten old books on software. And even those we haven’t read.

Are there new books being published worth reading? Of course. The purpose of the heuristic is to offset the massive bias for selecting new books over old books. New books are but a fraction of all the books we have to choose from.

There is an endless stream of well-groomed advice coming out of Silicon Valley. Typical authors of Silicon Valley self-help books are former employees or consultants at one of the big tech companies, like Amazon or Google, or a VC investor or consultant for start-up companies. Essentially it is the winners of capitalism writing down their recipes for success as an example for all, confirmation bias be damned. Sometimes it comes in the form of some radical pixie dust that you are supposed to sprinkle on top of your software organization to achieve bliss.

There are many reasons to sit out on Silicon Valley self-help books. One is that self-help books in general primarily help the authors. As always, the best way to get rich is to sell get-rich-schemes. Another is that many Silicon Valley self-help books are bestsellers, and so the heuristic to avoid bestsellers applies to them.

But there are other reasons as well, primary among them being that you are not them. Unless you are in Silicon Valley, you are not in Silicon Valley. Your culture is probably very different. Your context is probably very different. Your goals and your priorities are probably very different. The forces that contribute to success or failure are probably very different. Unless you’re a start-up working yourself and your compatriots to burn-out or IPO, you are not a start-up etc. Unless you are a technological mega-corp with a market cap larger than many countries, you are not a technological mega-crop etc. You are not them. So even if we set aside confirmation bias and attribution errors - the fact that we are typically poor judges of the causes of our own success or failure - why would we assume that what worked for them will work for us?

Of course, some of the tools and techniques and the pixie dust used in Silicon Valley may in fact be useful in other contexts as well. But it’s hard to take success in Silicon Valley as a guarantee for that.

When should you bite the bullet and read a Silicon Valley self-help book? It could of course be that you believe that the self-help book will be genuinely helpful. In that’s the case, by all means, go ahead. But beware that it’s a rather weak reason and that chances are you’ll be wrong. A better reason is the principle of know your enemy. That is, if a particularly stupid fad is getting an unreasonable amount of attention in your environment, you may find it useful to go to the sources and know and understand the fad better than those who promote it in your vicinity.

This sounds like patently bad advice, especially since I said that the context is books that a software professional might want to read to be better at their job. But it is a matter of personal experience. In my experience, the books that have had the greatest impact on my thinking were not books written by people in tech. The reason is that the books themselves were not about tech. It turns out that philosophers are better at philosophy than technologists. The same goes for sociologists and sociology, anthropologists and anthropology, etc.

Some of the books that I found most eye-opening are “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” by Jane Jacobs, “The Mismeasure of Man” by Stephen Gould, “Technopoly” by Neil Postman, “How Buildings Learn” by Steward Brant, “Seeing Like a State” by James Scott, “The Systems Bible” by John Gall, and “The Reflective Practitioner” by Donald Schön.

Obviously, there are many exceptions to this heuristic. An overriding heuristic is that books by Gerald Weinberg are usually good, and that even the mediocre ones are better than most. Some other great books about technology and programming include “Exercises in Programming Style” by Cristina Lopes, “Data and Reality” by William Kent, “Computer Power and Human Reason” by Joseph Weizenbaum, “The Little Schemer” by Friedman and Felleisen, “Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs” by Sussman and Abelson, and “Coders at Work” by Peter Seibel.

This one is rather obvious, but I feel like I have to address it.

There’s a wave of people who share their AI-fueled hyperproductivity life hacks. One of these hacks is to use LLMs to summarize books into bullet points. This then enables them to consume the entire British Library within a week.

These are obviously people who have never read a book in their life. I’m not going to say that they’ve never turned the pages of a book, ever, but they haven’t read them. If they had, they would have known better, or been too ashamed to spout such ridiculous nonsense.

What’s true, though, is that there are some books that should have been a blog post. In reality, often they were. Sometimes the author of a popular blog post or article may be approached by a publisher asking them to expand the idea into a book. This is easier said than done, and so the expansion is mostly hot air, artificially inflating the text to book length by diluting it. This means that at least in principle, the book can be summarized back into its original length without much loss. But it seems like a rather unnecessary and stupid little dance to go through.

Either way, these books are not the ones you want to read. The books you want to read cannot be compressed.

I’m all out of heuristics. It seems fitting to circle around to ask why we should read books in the first place.

The best books shake our neurons around, change the way to we think, change the way we see the world, give us new eyes and ears, new thoughts fluttering around inside our skulls. The purpose of my heuristics is to weed out books that are likely to be boring and useless, books that will leave you unchanged. I hope the heuristics might inspire you to pick up an unlikely book as your next read.