July 5, 2014

In the previous blog posts, we saw that we could hide the problematic concrete exception type from the C# compiler by tucking it inside a transformation from a closure of type Func<TR> to another closure of the same type. But of course we can use such transformations for many things besides exception handling. Any old behaviour that we would like to throw on top of the business logic, we can apply in layers using this approach.

This capability is so cool that I took a break from writing this blog post to share my enthusiasm with my wife. She was like, “what are you blogging about?”, and I was like “there’s this really cool thing you can do, where you apply this transformation to some method call, and then you can like, do additional stuff with it, entirely transparently!”, and she was like “like what?”, and I was like “like anything!”, and she was like “like what?”, and I was like “anything you want!”, but she was still like “like what though?” and then I turned more like “uh… uh… like say you had this method that returned a string - you could easily transform that into a method that looked exactly the same, but returned the reversed string instead”, and she was like “…the reversed string? why?” and I was like “or-or-or maybe you could return the uppercase string instead…?”, and she was like “uppercase?” with totally uppercase eyebrows and I was like “nonono! I got it! say you had this method that did a really expensive and slow computation, you could turn that into a method that would keep along the result that computation, so you didn’t have to do the actual computation all the time”, and she was like “oh, that’s cool” and I was like “phew! I’m never talking to her about blogging again!”.

So that was a close call. But yes, you can totally use this for caching. All we need is a suitable transformation thing.

public static Func<T> Caching<T>(this Func<T> f)

{

bool cached = false;

T t = default(T);

return () => {

if (cached) return t;

t = f();

cached = true;

return t;

};

}

Here, we’re taking advantage of the fact that C# has mutable closures - that is, that we can write to cached and t from inside the body of the lambda expression.

To verify that it works, we need a suitable example - something that’s really expensive and slow to compute. And as we all know, one of the most computationally intensive things we can do in a code example is to sleep:

Func<string> q = () => {

Thread.Sleep(2000);

return "Hard-obtained string";

};

Console.WriteLine(q());

Console.WriteLine(q());

Console.WriteLine(q());

q = q.Caching();

Console.WriteLine(q());

Console.WriteLine(q());

Console.WriteLine(q());

Well, what kind of behaviour should we expect from this code? Obviously, the first three q calls will be slow. But what about the three last? The three last execute the caching closure instead. When we execute the forth call, cached is false, and so the if test fails, and we proceed to evaluate the original, non-caching q (which is slow), tuck away the result value for later, set the cached flag to true, and return the computed result - the hard-obtained string. But the fifth and sixth calls should be quick, since cached is now true, and we have a cached result value to return to the caller, without ever having to resort to the original q.

That’s theory. Here’s practice:

So that seems to work according to plan. What else can we do? We’ve seen exception handling in the previous posts and caching in this one - both examples of so-called “cross-cutting concerns” in our applications. Cross-cutting concerns was hot terminology ten years ago, when the enterprise world discovered the power of the meta-object protocol (without realizing it, of course). It did so in the guise of aspect-oriented programming, which carried with it a whole vocabulary besides the term “cross-cutting concerns” itself, including “advice” (additional behaviour to handle), “join points” (places in your code where the additional behaviour may be applied) and “pointcuts” (a way of specifying declaratively which join points the advice applies to). And indeed, we can use these transformations that we’ve been doing to implement a sort of poor man’s aspects.

Why a poor man’s aspects? What’s cheap about them? Well, we will be applying advice at various join points, but we won’t be supporting pointcuts to select them. Rather, we will be applying advice to the join points manually. Arguably, therefore, it’s not really aspects at all, and yet we get some of the same capabilities. That’s why we’ll call them aspects without aspects. Makes sense?

Let’s consider wrapping some closure f in a hypothetical try-finally-block, and see where we might want to add behaviour.

// 1. Before calling f.

try {

f();

// 2. After successful call to f.

}

finally {

// 3. After any call to f.

}

So we’ll create extension methods to add behaviour in those three places. We’ll call them Before, Success and After, respectively.

public static class AspectExtensions {

public static Func<T> Before<T>(this Func<T> f, Action a) {

return () => { a(); return f(); };

}

public static Func<T> Success<T>(this Func<T> f, Action a) {

return () => {

var result = f();

a();

return result;

};

}

public static Func<T> Success<T>(this Func<T> f, Action<T> a) {

return () => {

var result = f();

a(result);

return result;

};

}

public static Func<T> After<T>(this Func<T> f, Action a) {

return () => {

try {

return f();

} finally {

a();

}

};

}

public static Func<T> After<T>(this Func<T> f, Action<T> a) {

return () => {

T result = default(T);

try {

result = f();

return result;

} finally {

a(result);

}

};

}

}

Note that we have two options for each of the join points that occur after the call to the original f closure. In some cases you might be interested in the value returned by f, in others you might not be.

How does it work in practice? Let’s look at a contrived example.

static void Main (string[] args)

{

Func<Func<string>, Func<string>> wrap = fn => fn

.Before(() => Console.WriteLine("I'm happening early on."))

.Success(r => Console.WriteLine("Successfully obtained: " + r))

.Before(() => Console.WriteLine("When do I occur???"))

.After(r => Console.WriteLine("What did I get? " + r));

var m1 = wrap(() => {

Console.WriteLine("Executing m1...");

return "Hello Kiczales!";

});

var m2 = wrap(() => {

Console.WriteLine("Executing m2...");

throw new Exception("Boom");

});

Call("m1", m1);

Call("m2", m2);

}

static void Call(string name, Func<string> m) {

Console.WriteLine(name);

try {

Console.WriteLine(name + " returned: " + m());

}

catch (Exception ex) {

Console.WriteLine("Exception in {0}: {1}", name, ex.Message);

}

Console.WriteLine();

}

So here we have a transformation thing that takes a Func<string> closure and returns another Func<string> closure, with several pieces of advice applied. Can you work out when the different closures will be executed?

We start with some closure fn, but before fn executes, the first Before must execute (that’s why we call it Before!). Assuming both of these execute successfully (without throwing an exception), the Success will execute. But before all these things, the second Before must execute! And finally, regardless of how the execution turns out with respect to exceptions, the After should execute.

In the case of m1, no exception occurs, so we should see the message “Successfully obtained: Hello Kiczales!” in between “Executing m1…” and “What did I get? Hello Kiczales!”. In the case of m2, on the other hand, we do get an exception, so the Success closure is never executed.

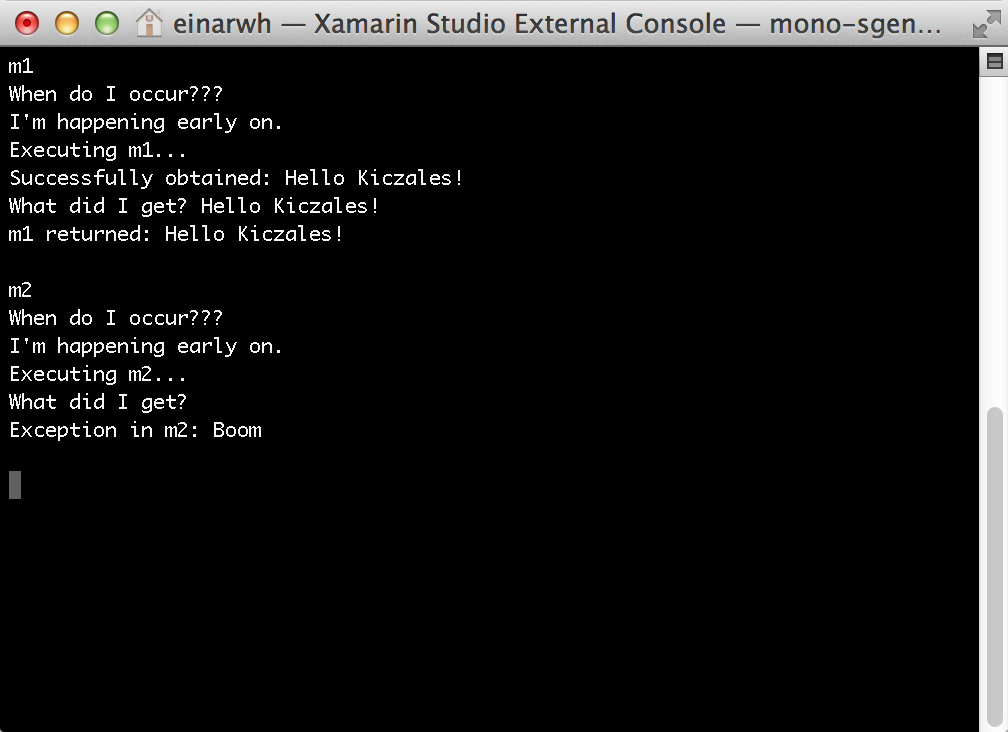

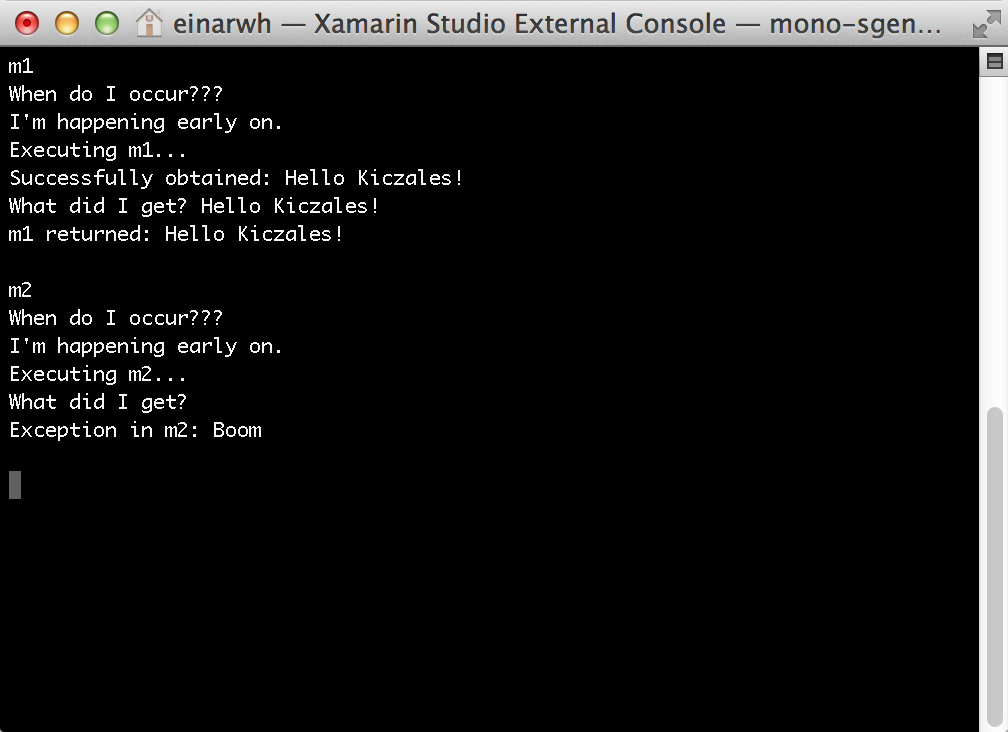

A screenshot of my console verifies this:

So we’ve seen that we can do fluent exception handling, caching and aspects without aspects using the same basic idea: we take something of type Func<TR> and produce something else of the same type. Of course, this means that we’re free to mix and match all of these things if we wanted to, and compose them all using Linq’s Aggregate method! For once, though, I think I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.

And of course, we can transform other things besides closures as well - we can use the same approach to transform any instance of type T to some other T instance. In fact, let’s declare a delegate to capture such a generalized concept:

delegate T Decorate<T>(T t);

Why Decorate? Well, nothing is ever new on this blog. I’m just rediscovering old ideas and reinventing flat tires as Alan Kay put it. In this case, it turns out that all we’ve been doing is looking at the good old Decorator pattern from the GoF book in a new or unfamiliar guise.