December 19, 2013

It appears I’ve been waiting in vain! It’s been more than a month since my last blog post, and still no pull requests for TailCop! In particular, no pulls requests that implement rewriting of recursive calls to loops for instance methods. I don’t know why.

I guess it’s up to me, then.

To recap, TailCop is a simple utility I wrote to rewrite tail-recursive static methods to use loops instead (which prevents stack overflow in cases where the recursion goes very deep). The reason we shied away from instance methods last time is dynamic dispatch, which complicates matters a bit. We’ll tackle that in this blog post. To do so, however, we need to impose a couple of constraints.

First, we need to make sure that the instance method is non-virtual, that is, that it cannot be overridden in a subclass. Why? Well, let’s suppose you let Add be virtual, so that people may override it. Sounds reasonable? If it isn’t overridden, then it will behave just the same whether or not it’s rewritten. If it is overridden, then it shouldn’t matter if we override the recursive or the rewritten version, right? Well, you’d think, but unfortunately that’s not the case.

Say you decided to make Add virtual and rewrote it using TailCop. A few months pass by. Along comes your enthusiastic, dim-witted co-worker, ready to redefine the semantics of Add. He’s been reading up on object-orientation and is highly motivated to put all his hard-won knowledge to work. Unfortunately, he didn’t quite get to the Liskov thing, and so he ends up with this:

class Adder

{

virtual int Add(int x, int y)

{

return x > 0 ? Add(x - 1, y + 1) : y;

}

}

class BlackAdder : Adder

{

override int Add(int x, int y)

{

return base.Add(x, x > 0 ? y + 1 : y);

}

}

So while he overrides the Add method in a subclass, he doesn’t replace it wholesale - he still invokes the original Add method as well. But then we have a problem. Due to dynamic dispatch, the recursive Add call in Adder will invoke BlackAdder.Add which will then invoke Adder.Add and so forth. Basically we’re taking the elevator up and down in the inheritance hierarchy. If we rewrite Adder.Add to use a loop, we will never be allowed to take the elevator back down to BlackAdder.Add. Obviously, then, the rewrite is not safe. Running BlackAdder.Add(30, 30) yields 90 with the original recursive version of Adder.Add and 61 with the rewritten version. Long story short: we will not rewrite virtual methods.

Our second constraint is that, obviously, the recursive call has to be made on the same object instance. If we call the same method on a different instance, there’s no guarantee that we’ll get the same result. For instance, if the calculation relies on object state in any way, we’re toast. So we need to invoke the method on this, not that. So how do we ensure that a recursive call is always made on the same instance - that is, on this? Well, obviously we need to be in a situation where the evaluation stack contains a reference to this in the right place when we’re making the recursive call. In IL, the this parameter to instance methods is always passed explicitly, unlike in C#. So a C# instance method with n parameters is represented as a method with n+1 parameters on the IL level. The additional parameter in IL is for the this reference, and is passed as the first parameter to the instance method. (This is similar to Python, where the self parameter is always passed explicitly to instance methods.) So anyways, if we take the evaluation stack at the point of a call to an instance methods and pop off n values (corresponding to the n parameters in the C# method), we should find a this there. If we find something else, we won’t rewrite.

While the first constraint is trivial to check for, the second one is a bit more involved. What we have at hand is a data-flow problem, which is a big thing in program analysis. In our case, we need to identify places in the code where this references are pushed onto the stack, and emulate how the stack changes when different opcodes are executed. To model the flow of data in a method (in particular: flow of this references), we first need to construct a control flow graph (CFG for short). A CFG shows (statically) the different possible execution paths through the method. It consists of nodes that represents blocks of instructions and edges that represents paths from one such block to another. A method without branching instructions has a trivial CFG, consisting of a single node representing a block with all the instructions in the method. Once we have branching instructions, however, things become a little more interesting. For instance, consider the code below:

public static int Loop(int x, int y)

{

while (x > 0)

{

-x;

++y;

}

return y;

}

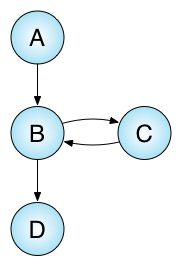

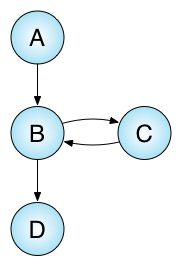

The CFG for (the IL representation of) that code looks like this:

As you can see, some nodes now have multiple inbound edges. This matters when we try to describe how data flows through the method. Let’s see if we can sketch it out by looking at what happens inside a single node first. A node represents a block of n instructions. Each instruction can be thought of as a function f : S -> S’ that accepts a stack as input and produces a stack as output. We can then produce an aggregated stack transformation function for an entire node in the CFG by composing such functions. Since each node represents a block of n instructions, we have a corresponding sequence of functions f0, f1, …, fn-1 of stack transformations. We can use this sequence to compose a new function g : S -> S’ by applying each function fi in order, as follows: g(s) = fn-1(…(f1(f0(s)))). In superior languages, this is sometimes written g = fn-1 o … o f1 o f0, where o is the composition operator.

Each node in the CFG is associated with such a transformation function g. Now the edges come into play: since it is possible to arrive at some node n in the CFG by following different paths, we may end up with more than a single stack as potential input for n’s g function - and hence more than a single stack as potential output. In general, therefore, we associate with each node a set I of distinct input stacks and a set O of distinct output stacks. Obviously, if there is an edge from node n to node m in CFG, then all stacks in n’s output set will be elements in m’s input set. To determine the sets I and O for each node in the CFG, we traverse the edges in the CFG until the various I’s and O’s stabilize, that is, until we no longer produce additional distinct stacks in any of the sets.

This gives us the following pseudocode for processing a node in the CFG, given a set S of stacks as input:

def process S

if exists s in S where not I contains s

I = I union S

O = map g I

foreach e in edges

process e.target O

end

end

end

Initially, I and O for all nodes will be empty sets. We start processing at the entry node, with S containing just the empty stack. When we’re done, each node will have their appropriate sets I and O.

So now we have the theory pretty much in place. We still need a way to dermine the potential stack state(s) at the place in the code where it matters, though: at the call instruction for the recursive method call. It’s very easy at this point - we already have all the machinery we need. Assuming that a recursive call happens as the k’th instruction in some node, all we have to do is compose the function h(s) = fk-1(…f1(f0(s))), alternatively h = fk-1 o … o f1 o f0. Mapping h onto the stack elements of the node’s I set, we get a set C of stack elements at the call site. Now we pop off any “regular” argument values for the method call off the stacks in C to produce a new set C'. Finally we verify that for all elements in C', we have a this reference at the top of the stack.

Now we should be in good shape to tackle the practicalities of our implementation. One thing we obviously need is a data type to represent our evaluation stack - after all, our description above is littered with stack instances. The stack can be really simple, in that it only needs to distinguish between two kinds of values: this and anything else. So it’s easy, we’ll just use the plain ol’ Stack<bool>, right? Unfortunately we can’t, since Stack<bool> is mutable (in that push and pop mutate the stack they operate on). That’s definitely not going to work. When producing the stack instances in O, we don’t want the g function to mutate the actual stack instances in I in the process. We might return later on with stack instances we’ll want to compare to the instances in I, so we need to preserve those as-is. Hence we need an immutable data structure. So we should use ImmutableStack<bool> from the Immutable Collections, right? I wish! Unfortunately, ImmutableStack<bool>.Equals has another problem (which Stack<bool> also has) - it implements reference equality, whereas we really need value equality (so that two distinct stack instances containing the same values are considered equal). So I ended up throwing together my own EvalStack class instead, highly unoptimized and probably buggy, but still serving our needs.

class EvalStack

{

private const char YesThis = '1';

private const char NotThis = '0';

private readonly string _;

private EvalStack(string s) { _ = s; }

public EvalStack() : this("") {}

public bool Peek()

{

if (IsEmpty)

{

throw new Exception("Cannot Peek an empty stack.");

}

return _[0] == YesThis;

}

public EvalStack Pop()

{

if (IsEmpty)

{

throw new Exception("Cannot Pop an empty stack.");

}

return new EvalStack(_.Substring(1));

}

public EvalStack Push(bool b)

{

char c = b ? YesThis : NotThis;

return new EvalStack(c + _);

}

public bool IsEmpty

{

get { return _.Length == 0; }

}

public override bool Equals(object that)

{

return Equals(that as EvalStack);

}

public bool Equals(EvalStack that)

{

return _.Equals(that._);

}

public override int GetHashCode()

{

return (_ != null ? _.GetHashCode() : 0);

}

public override string ToString()

{

return "[" + _ + "]";

}

}

I’m particularly happy about the way the code for the ToString method ended up.

Now that we have a data structure for the evaluation stack, we can proceed to look at how to implement the functions f : S -> S’ associated with each instruction in the method body. At first glance, this might seem like a gargantuan task - in fact, panic might grip your heart - as there are rather a lot of different opcodes in IL. I haven’t bothered to count them, but it’s more than 200. Luckily, we don’t have to implement unique functions for all of them. Instead, we’ll treat groups of them in bulk. At a high level, we’ll distinguish between three groups of instructions: generators, propagators and consumers.

The generators are instructions that conjure up this references out of thin air and push them onto the stack. The prime example is ldarg.0 which loads the first argument to the method and pushes it. For instance methods, the first argument is always this. In addition to ldarg.0, there are a few other instructions that in principle could perform the same task (such as ldarg n).

The propagators are instructions that can derive or pass on a this reference from an existing this reference. The dup instruction is such an instruction. It duplicates whatever is currently at the top of the stack. If that happens to be a this reference, the result will be this references at the two topmost locations in the stack.

The vast majority of the instructions, however, are mere consumers in our scenario. They might vary in their exact effect on the stack (how many values they pop and push), but they’ll never produce a this reference. Hence we can treat them generically, as long as we know the number of pops and pushes for each - we’ll just pop values regardless of whether or not there they are this references, and we’ll push zero or more non-this values onto the stack.

At this point, it’s worth considering the soundness of our approach. In particular, what happens if I fail to identify a generator or a propagator? Will the resulting code still be correct? Yes! Why? Because we’re always erring on the conservative side. As long as we don’t falsely produce a this reference that shouldn’t be there, we’re good. Failing to produce a this reference that should be there is not much of a problem, since the worst thing that can happen is that we miss a tail call that could have been rewritten. For instance, I’m not even bothering to try to track this references that are written to fields with stflda (for whatever reason!) and then read back and pushed onto the stack with ldflda.

Does this mean TailCop is safe to use and you should apply it to your business critical applications to benefit from the immense speed benefits and reduced risk for stack overflows that stems from rewriting recursive calls to loops? Absolutely not! Are you crazy? Expect to find bugs, oversights and gaffes all over the place. In fact, TailCop is very likely to crash when run on code examples that deviate much at all from the simplistic examples found in this post. All I’m saying is that the principles should be sound.

Mono.Cecil does try to make our implementation task as simple as possible, though. The OpCode class makes it almost trivial to write f-functions for most consumers - which is terrific news, since so many instructions end up in that category. Each OpCode in Mono.Cecil knows how many values it pops and pushes, and so we can easily compose each f from the primitive functions pop and push. For instance, assume we want to create the function fadd for the add instruction. Since Mono.Cecil is kind enough to tell us that add pops two values and pushes one value, we’ll use that information to compose the function fadd(s) = push(*non-this*, pop(pop(s))).

Here’s how we compose such f-functions for consumer instructions in TailCop:

public Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> CreateConsumerF(int pops, int pushes)

{

Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> pop = stack => stack.Pop();

Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> push = stack => stack.Push(false);

Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> result = stack => stack;

for (int i = 0; i < pops; i++)

{

var fresh = result;

result = stack => pop(fresh(stack));

}

for (int i = 0; i < pushes; i++)

{

var fresh = result;

result = stack => push(fresh(stack));

}

return result;

}

Notice the two fresh variables, which are there to avoid problems related to closure modification. Eric Lippert explains the problem here and here. TL;DR is: we need a fresh variable to capture each intermediate result closure.

We’ll call the CreateConsumerF method from the general CreateF method which also handles generators and propagators. The simplest possible version looks like this:

private Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> CreateF(Instruction insn)

{

var op = insn.OpCode;

if (op == OpCodes.Ldarg_0)

{

// Prototypical *this* generator!!

return stack => stack.Push(true);

}

if (op == OpCodes.Dup)

{

// Prototypical *this* propagator!!

return stack => stack.Push(stack.Peek());

}

return CreateConsumerF(insn);

}

You’ll note that I’ve only included a single generator and a single propagator! I might add more later on. The minimal CreateF version is sufficient to handle our naïve Add method though.

Now that we have a factory that produces f-functions for us, we’re all set to compose g-functions for each node in the CFG.

private Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> CreateG()

{

return CreateComposite(_first, _last);

}

private Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> CreateComposite(

Instruction first,

Instruction last)

{

Instruction insn = first;

Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> fun = stack => stack;

while (insn != null)

{

var f = CreateF(insn);

var fresh = fun;

fun = stack => f(fresh(stack));

insn = (insn == last) ? null : insn.Next;

}

return fun;

}

Once we have the g-function for each node, we can proceed to turn the pseudocode for processing nodes into actual C# code. In fact the C# code looks remarkably similar to the pseudocode.

public void Process(ImmutableHashSet<EvalStack> set)

{

var x = set.Except(_I);

if (!x.IsEmpty)

{

_I = _I.Union(x);

_O = _I.Select(s => G(s)).ToImmutableHashSet();

foreach (var n in _targets)

{

n.Process(_O);

}

}

}

We process the nodes in the CFG, starting at the root node, until the I-sets of input stacks and the O-sets of output stacks stabilize. At that point, we can determine the stack state (with respect to this references) for any given instruction in the method - including for any recursive method call. We determine whether or not it is safe to rewrite a recursive call to a loop like this:

public bool SafeToRewrite(Instruction call,

Dictionary<Instruction, Node> map)

{

var insn = call;

while (!map.Keys.Contains(insn))

{

insn = insn.Previous;

}

var node = map[insn];

var stacks = node.GetPossibleStacksAt(call);

var callee = (MethodReference)call.Operand;

var pops = callee.Parameters.Count;

return stacks.Select(s =>

{

var st = s;

for (int i = 0; i < pops; i++)

{

st = st.Pop();

}

return st;

}).All(s => s.Peek());

}

We find the node that the call instruction belongs to, find the possible stack states at the call site, pop off any values intended to be passed as arguments to the method, and verify that we find a this reference at the top of each stack. Simple! To find the possible stack states, we need to compose the h-function for the call, but that’s easy at this point.

ImmutableHashSet<EvalStack> GetPossibleStacksAt(Instruction call)

{

var h = CreateH(call);

return _I.Select(h).ToImmutableHashSet();

}

Func<EvalStack, EvalStack> CreateH(Instruction call)

{

return CreateComposite(_first, call.Previous);

}

And with that, we’re done. Does it work? It works on my machine. You’ll have to download TailCop and try for yourself.