November 5, 2013

Last week I was at the TDC conference in Trondheim to do a talk entitled “Bytecode for beginners”. In one of my demos, I showed how you might do a limited form of tail call elimination using bytecode manipulation. To appreciate what (recursive) tail calls are and why you might want to eliminate them, consider the following code snippet:

static int Add(int x, int y)

{

return x > 0 ? Add(x - 1, y + 1) : y;

}

As you can see, it’s a simple recursive algorithm to add two (non-negative) integers together. Yes, I am aware that there is a bytecode operation available for adding integers, but let’s forget about such tedious practicalities for a while. It’s just there to serve as a minimal example of a recursive algorithm. Bear with me.

The algorithm exploits two simple facts:

So basically we just decrement x and increment y until we run out of x, and then all we have left is y. Pretty simple.

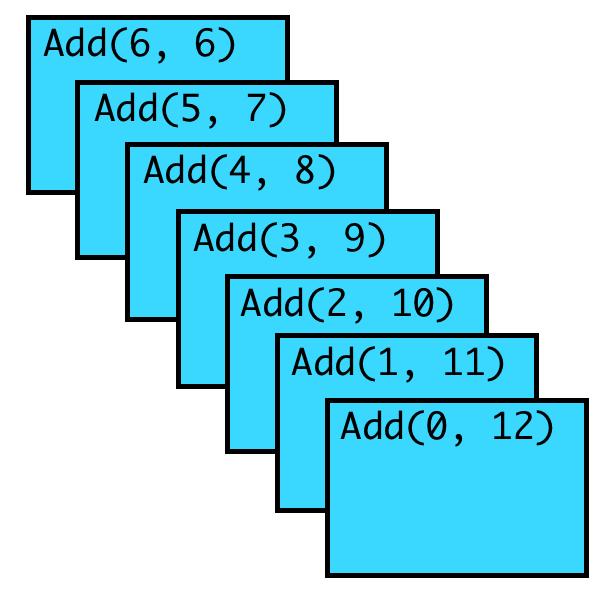

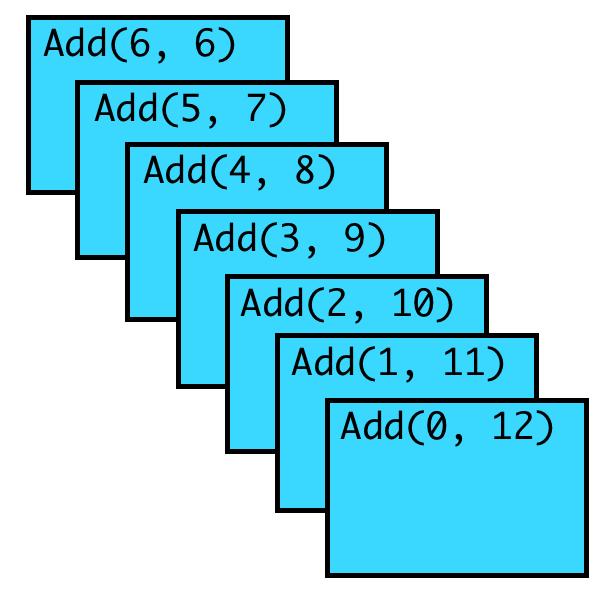

This algorithm works really well for lots of integers, but the physical world of the computer puts a limit on how big x can be. The problem is this: each time we call Add, the .NET runtime will allocate a bit of memory known as a stack frame for the execution of the method. To illustrate, consider the addition of two small numbers, 6 + 6. If we imagine the stack frames -uh- stacked on top of each other, it might look something like this:

So we allocate a total of 7 stack frames to perform the calculation. The .NET runtime will handle that just fine, but 6 is a pretty small number. In general we allocate x + 1 stack frames, and at some point that becomes a problem. The .NET runtime can only accommodate so many stack frames before throwing in the towel (where the towel takes on the physical form of a StackOverflowException).

It’s worth noting, though, that all we’re really doing in each of the stack frames leading up to Add(0, 12) is wait around for the result of the next invocation of Add to finish, and when we get that result, that’s immediately what is returned as result from the current stack frame.

This is what is known as a tail recursive call. In general, a tail call is any call in tail position, that is, any call that happens as the last operation of a method. It may be a call to the same method (as in our example) or it may be a call to some other method. In either case, we’re making a method call at a point in time where we don’t have much need for the old stack frame anymore.

It should come as no surprise, therefore, that clever people have figured out that in principle, we don’t need a brand new stack frame for each tail call. Instead, we can reuse the old one, slightly modified, and simply jump to the appropriate method. This is known as tail call optimization or tail call elimination. You can find all the details in a classic paper by the eminent Guy L Steele Jr. The paper has the impressive title DEBUNKING THE “EXPENSIVE PROCEDURE CALL” MYTH or PROCEDURE CALL IMPLEMENTATIONS CONSIDERED HARMFUL or LAMBDA: THE ULTIMATE GOTO, but is affectionately known as simply Lambda: The Ultimate GOTO (presumably because overly long and complex titles are considered harmful).

In this blog post, we’ll implement a poor man’s tail call elimination by transforming recursive tail calls into loops. Instead of actually making a recursive method call, we’ll just jump to the start of the method - with the arguments to the method set to the appropriate values. That’s actually remarkably easy to accomplish using bytecode rewriting with the ever-amazing Mono.Cecil library. Let’s see how we can do it.

First, we’ll take a look at the original bytecode, the one that does the recursive tail call.

.method private hidebysig static

int32 Add(

int32 x,

int32 y

) cil managed

{

// Code size 17 (0x11)

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: brtrue.s IL_0005

IL_0003: ldarg.1

IL_0004: ret

IL_0005: ldarg.0

IL_0006: ldc.i4.1

IL_0007: sub

IL_0008: ldarg.1

IL_0009: ldc.i4.1

IL_000a: add

IL_0012: call int32 Program::Add(int32,int32)

IL_0013: ret

} // end of method Program::Add

So the crucial line is at IL_0012, that’s where the recursive tail call happens. We’ll eliminate the call instruction and replace it with essentially a goto. In terms of IL we’ll use a br.s opcode (where “br” means branch), with the first instruction (IL_0000) as target. Prior to jumping to IL_0000, we need to update the argument values for the method. The way method calls work in IL is that the argument values have been pushed onto the execution stack prior to the call, with the first argument deepest down in the stack, and the last argument at the top. Therefore we already have the necessary values on the execution stack, it is merely a matter of writing them to the right argument locations. All we need to do is starg 1 and starg 0 in turn, to update the value of y and x respectively.

.method private hidebysig static

int32 Add (

int32 x,

int32 y

) cil managed

{

// Method begins at RVA 0x2088

// Code size 18 (0x12)

.maxstack 8

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldc.i4.0

IL_0002: bgt.s IL_0006

IL_0004: ldarg.1

IL_0005: ret

IL_0006: ldarg.0

IL_0007: ldc.i4.1

IL_0008: sub

IL_0009: ldarg.1

IL_000a: ldc.i4.1

IL_000b: add

IL_0010: starg 1

IL_0011: starg 0

IL_0012: br.s IL_0000

} // end of method Program::Add

If we reverse engineer this code into C# using a tool like ILSpy, we’ll see that we’ve indeed produced a loop.

private static int Add(int x, int y)

{

while (x != 0)

{

int arg_0F_0 = x - 1;

y++;

x = arg_0F_0;

}

return y;

}

You may wonder where the arg_0F_0 variable comes from; I do too. ILSpy made it up for whatever reason. There’s nothing in the bytecode that mandates a local variable, but perhaps it makes for simpler reverse engineering.

Apart from that, we note that the elegant recursive algorithm is gone, replaced by a completely pedestrian and mundane one that uses mutable state. The benefit is that we no longer run the risk of running out of stack frames - the reverse engineered code never allocates more than a single stack frame. So that’s nice. Now if we could do this thing automatically, we could have the best of both worlds: we could write our algorithms in the recursive style, yet have them executed as loops. That’s where TailCop comes in.

TailCop is a simple command line utility I wrote that rewrites some tail calls into loops, as in the example we’ve just seen. Why some and not all? Well, first of all, rewriting to loops doesn’t help much for mutually recursive methods, say. So we’re restricted to strictly self-recursive tail calls. Furthermore, we have to be careful with dynamic dispatch of method calls. To keep TailCop as simple as possible, I evade that problem altogether and don’t target instance methods at all. Instead, TailCop will only rewrite tail calls for static methods. (Obviously, you should feel free, even encouraged, to extend TailCop to handle benign cases of self-recursive instance methods, i.e. cases where the method is always invoked on the same object. Update: I’ve done it myself.)

The first thing we need to do is find all the recursive tail calls.

private IList<Instruction> FindTailCalls(MethodDefinition method)

{

var calls = new List<Instruction>();

foreach (var insn in method.Body.Instructions)

{

if (insn.OpCode == OpCodes.Call)

{

var methodRef = (MethodReference)insn.Operand;

if (methodRef == method)

{

if (insn.Next != null && insn.Next.OpCode == OpCodes.Ret)

{

calls.Add(insn);

}

}

}

}

return calls;

}

So as you can see, there’s nothing mystical going on here. We’re simply selecting call instructions from method bodies where the invoked method is the same as the method we’re in (so it’s recursive) and the following instruction is a ret instruction.

The second (and final) thing is to do the rewriting described above.

private void TamperWith(

MethodDefinition method,

IEnumerable<Instruction> calls)

{

foreach (var call in calls)

{

var il = method.Body.GetILProcessor();

int counter = method.Parameters.Count;

while (counter > 0)

{

var starg = il.Create(OpCodes.Starg, -counter);

il.InsertBefore(call, starg);

}

var start = method.Body.Instructions[0];

var loop = il.Create(OpCodes.Br_S, start);

il.InsertBefore(call, loop);

il.Remove(call.Next); // Ret

il.Remove(call);

}

}

As you can see, we consistently inject new instructions before the recursive call. There are three things to do:

That’s all there is to it. If you run TailCop on an assembly that contains the tail recursive Add method, it will produce a new assembly where the Add method contains a loop instead. Magic!

To convince ourselves (or at least make it plausible) that TailCop works in general, not just for the Add example, let’s consider another example. It looks like this:

private static int Sum(List<int> numbers, int result = 0)

{

int size = numbers.Count();

if (size == 0)

{

return result;

}

int last = size - 1;

int n = numbers[last];

numbers.RemoveAt(last);

return Sum(numbers, n + result);

}

So once again we have a tail recursive algorithm, this time to compute the sum of numbers in a list. It would be sort of nice and elegant if it were implemented in a functional language, but we’ll make do. The idea is to exploit two simple facts about sums of lists of integers:

The only complicating detail is that we use an accumulator (the result variable) in order to make the implementation tail-recursive. That is, we pass the partial result of summing along until we run out of numbers to sum, and then the result is complete. But of course, this algorithm is now just a susceptible to stack overflows as the recursive Add method was. And so we run TailCop on it to produce this instead:

private static int Sum(List<int> numbers, int result = 0)

{

while (true)

{

int num = numbers.Count<int>();

if (num == 0)

{

break;

}

int index = num - 1;

int num2 = numbers[index];

numbers.RemoveAt(index);

List<int> arg_27_0 = numbers;

result = num2 + result;

numbers = arg_27_0;

}

return result;

}

And we’re golden. You’ll note that ILSpy is just about as skilled at naming things as that guy you inherited code from last month, but there you go. You’re not supposed to look at reverse engineered code, you know.