February 15, 2013

If you’ve ever created an ASP.NET MVC application, chances are you’ve used data annotation validators to validate user input to your models. They’re nice, aren’t they? They’re so easy to use, they’re almost like magic. You simply annotate your properties with some declarative constraint, and the good djinns of the framework provide both client-side validation and server-side validation for you. Out of thin air! The client-side validation is implemented in JavaScript and gives rapid feedback to the user during data entry, whereas the server-side validation is implemented in .NET and ensures that the data is valid even if the user should circumvent the client-side validation somehow (an obvious approach would be to disable JavaScript in the browser). Magical.

The only problem with data annotation validators is that they are pretty limited in their semantics. The built-in validation attributes only cover a few of the most common, basic use cases. For instance, you can use the [Required] attribute to ensure that a property is given a value, the [Range] attribute to specify that the property of a value must be between two constant values, or the [RegularExpression] attribute to specify a regular expression that a string property must match. That’s all well and good, but not really suited for sophisticated validation. In case you have stronger constraints or invariants for your data model, you must reach for one of two solutions. You can use the [Remote] attribute, which allows you to do arbitrary validation at the server. In that case, however, you’re doing faux-client-side validation. What really happens behind the scenes is that you fire off an AJAX call to the server. The alternative is to implement your own custom validation attribute, and write validation logic in both .NET and in JavaScript. However, that quickly becomes tiresome. While your custom attribute certainly can do arbitrary model validation, you’ve ended up doing the work that the djinns should be doing for you. There is no magic any more, there is just grunt work. The spell is broken.

Wouldn’t it be terribly nifty if there were some way to just express your sophisticated rules and constraints declaratively as intended, and have someone else do all the hard work? That’s what I thought, too. At this point, you shouldn’t be terribly surprised to learn that such a validation attribute does, in fact, exist. I’ve made it myself. The attribute is called Mkay, and supports a simple rule DSL for expressing pretty much arbitrary constraints on property values using a LISP-like syntax. Why LISP, you ask? For three obvious reasons:

So that’s the syntax, but exactly what kinds of rules can you express using the Mkay rule DSL? Well, that’s pretty much up to you - that’s the whole point, after all. In an Mkay expression, you can have constant values, property access (to any property on the model), logical operators (and and or), comparison operators (equality, greater-than, less-than and so forth), arithmetic, and a handful of simple functions (such as len for string length, max for selecting max value, now for the current time etc). It’s not too hard to extend it to support additional functions, but obviously they must then be implemented/wired up in JavaScript and .NET code. A contrived example should make it clearer:

public class Person

{

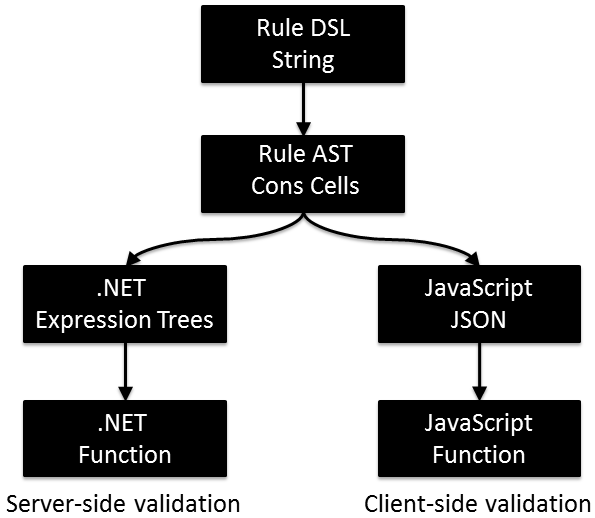

[Mkay("(< (len .) 5)", ErrorMessage = "That's too long, my friend.")]

public string Name { get; set; }

[Mkay("(>= . \"31.01.1900\")")]

public DateTime BirthDate { get; set; }

[Mkay("(<= . (now))")]

public DateTime DeathDate { get; set; }

[Mkay("(and (>= . BirthDate) (<= . DeathDate))")]

public DateTime LastSeen { get; set; }

}

In case it’s not terribly obvious, the rules indicate that the length of the Name property must be less than 10, the BirthDate must be later than 31.01.1900, the DeathDate must be before the current date, and LastSeen must understandably be some time between birth and death. Makes sense?

If you’ve never seen a LISP expression before, note that LISP operators are put in front of, rather than in between, the values they operate on. This is known as prefix notation as opposed to infix notation (or postfix notation, where the operator comes at the end). An expression like “(< . (now))” should be interpreted as “the value of the DeathDate property should be less than the value of (now)”. From this, you might deduce (correctly) that “.” is used as shorthand for the name of the property being validated. This is the first of three spoonfuls of syntactic sugar employed by Mkay to simplify the syntax for validation rules. The second spoonful is implicit “.” for comparisons, which means that you can actually write “(< (now))” instead of “(< . (now))”. And finally, the third spoonful lets you drop the outermost parentheses, so you end up with “< (now)”. Using simplified syntax, the example looks like this:

public class Person

{

[Mkay("< (len .) 5", ErrorMessage = "That's too long, my friend.")]

public string Name { get; set; }

[Mkay(">= \"31.01.1900\"")]

public DateTime BirthDate { get; set; }

[Mkay("<= (now)")]

public DateTime DeathDate { get; set; }

[Mkay("and (>= BirthDate) (<= DeathDate)")]

public DateTime LastSeen { get; set; }

}

So you can see that the sugar simplifies things quite a bit. Hopefully you’ll also agree that 1) the rules expressed in Mkay are more sophisticated than what the built-in validation attributes support, and 2) you’re pretty much free to write your own arbitrary rules using Mkay, without ever having to write a custom validation attribute again. The magic is back!

However, since this is a technical blog, let’s take a look under the covers to see how things work.

The crux of doing your own custom validation is to create a validation attribute that inherits from ValidationAttribute and implements IClientValidatable. Inheriting from ValidationAttribute is what lets us hook into the server-side validation process, whereas implementing IClientValidatable gives us a chance to send the necessary instructions to the browser to enable client-side validation. We’ll look at both of those things in turn. For now, though, let’s just concentrate on creating an instance of the validation attribute itself. In Mkay, the name of the validation attribute is MkayAttribute. No surprises there.

[AttributeUsage(AttributeTargets.Property, AllowMultiple = false, Inherited = true)]

public class MkayAttribute : ValidationAttribute, IClientValidatable

{

private readonly string _ruleSource;

private readonly string _defaultErrorMessage;

private readonly Lazy<ConsCell> _cell;

public MkayAttribute(string ruleSource)

{

_ruleSource = ruleSource;

_defaultErrorMessage = "Respect '{0}', mkay?".With(ruleSource);

_cell = new Lazy<ConsCell>(() => new ExpParser(ruleSource).Parse());

}

protected ConsCell Tree

{

get { return _cell.Value; }

}

public IEnumerable<ModelClientValidationRule> GetClientValidationRules(

ModelMetadata metadata, ControllerContext context) …

protected override ValidationResult IsValid(

object value, ValidationContext validationContext) …

}

The MkayAttribute constructor takes a single string parameter, which is supposed to contain a valid Mkay expression. Things will blow up at runtime if it doesn’t. The ExpParser class is responsible for parsing the Mkay expression into a suitable data structure known as an abstract syntax tree; AST for short. This happens lazily whenever someone tries to access the AST, which in practice means in the GetClientValidationRules and IsValid methods.

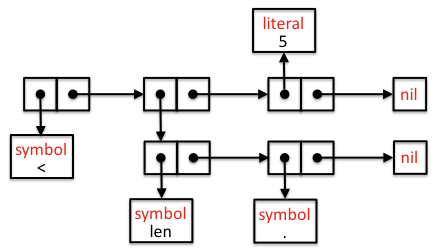

Due to LISP envy, ExpParser (simple as it is) uses lists and atoms as building blocks for the AST. Atoms represent simple things, such as a constant value (such as 10), the name of a property (such as BirthDate) or a symbol representing some operation (such as >). Lists are simply sequences of things, that is, sequences of lists and atoms. In Mkay, lists are built from so-called cons cells which are linked together in a chain. Each cons cell consists of two things, the first of which may be considered the content of the cell (a list or an atom), and the second of which is a reference to another cons cell or a special thing called Nil. So for instance, the Mkay expression “(< (len .) 5)” is represented by the following AST:

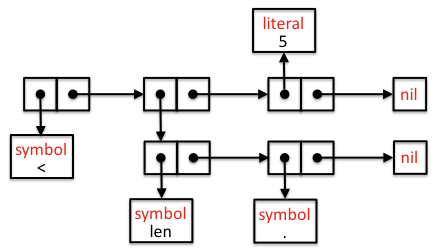

Once we have obtained the Mkay AST, we can use it to drive the client-side and server-side validations. This happens by subjecting the original AST to a two-pronged transformation process, to create two new, technology-specific AST’s: a .NET expression tree for the server-side validation code and a JSON structure for the client-side validation code. At the server side, the expression tree is compiled at runtime into a validation function that is immediately applied. The JSON structure, on the other hand, is sent to the browser where the jQuery validation machinery picks it up, and hands it over to what is essentially a validation function factory. So there’s code generation there, too, in a way, but it happens in the browser. Conceptually, the process looks like this:

Let’s look at server-side validation first. To participate in server-side validation, the MkayAttribute overrides the IsValid method inherited from ValidationAttribute. The implementation looks like this:

protected override ValidationResult IsValid(object value,

ValidationContext validationContext)

{

var subject = validationContext.ObjectInstance;

var memName = validationContext.MemberName;

if (memName == null)

{

throw new Exception(

"Property name is not set for property with display name "

+ validationContext.DisplayName

+ ", you should register the MkayValidator "

+ " with the MkayAttribute in global.asax.");

}

var validator = CreateValidator(subject, memName, Tree);

return validator()

? ValidationResult.Success

: new ValidationResult(ErrorMessage ?? _defaultErrorMessage);

}

private static Func<bool> CreateValidator(object subject,

string property,

ConsCell ast)

{

var builder = new ExpressionTreeBuilder(subject, property);

var viz = new ExpVisitor<Expression>(builder);

ast.Accept(viz);

var exp = viz.GetResult();

var validator = builder.DeriveFunc(exp).Compile();

return validator;

}

As you can see, the method is passed two parameters, an object called value and a ValidationContext called context. The value parameter is the value of the property we’re validating. The ValidationContext provides - uh - context for the validation, such as a reference to the full object. That’s a good thing, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to access the values of other properties and our efforts would be futile! However, we’re not entirely out of trouble - for some reason, there is no easy way to obtain the name of the property value belongs to! I presume it’s just a silly oversight by the good ASP.NET MVC folks. In fact, there is actually a MemberName property on the ValidationContext, but it is always null! There is a DisplayName which is populated, but that doesn’t have to be unique and hence isn’t a reliable pathway back to the actual parameter.

So what to do, what to do? A brittle solution to this very surprising problem would be to use reflection to flip through stack frames and figure out which property the current instance of the MkayAttribute was used to annotate. I’m sure I could get it to work most of the time. However, there’s a much simpler solution. Since ASP.NET MVC is open source, we can quite literally go to the source to find the root of the problem. In doing so, we find that the problem can be traced back to the Validate method in the DataAnnotationsModelValidator class. For whatever reason, the ValidationContext.MemberName property is not set, even though it would be trivial to do so (like, right before or after DisplayName is set). Luckily, ASP.NET MVC is thoroughly configurable, and so it is entirely possible to substitute your own DataAnnotationsModelValidator for the default one. So that’s what Mkay does:

public class MkayValidator : DataAnnotationsModelValidator<MkayAttribute>

{

public MkayValidator(ModelMetadata metadata,

ControllerContext context,

MkayAttribute attribute)

: base(metadata, context, attribute)

{}

public override IEnumerable<ModelValidationResult> Validate(object container)

{

var context = new ValidationContext(container ?? Metadata.Model, null, null)

{

DisplayName = Metadata.GetDisplayName(),

MemberName = Metadata.PropertyName

};

var result = Attribute.GetValidationResult(Metadata.Model, context);

if (result != ValidationResult.Success)

{

yield return new ModelValidationResult { Message = result.ErrorMessage };

}

}

}

Finally, the ASP.NET MVC application must be configured to use the replacement validator class. This happens in the Application_Start method in the MvcApplication class, aka global.asax:

public class MvcApplication : System.Web.HttpApplication

{

protected void Application_Start()

{

// … code omitted …

DataAnnotationsModelValidatorProvider.RegisterAdapter(

typeof(MkayAttribute),

typeof(MkayValidator));

}

}

In case you forget to wire up the custom validator (which would be terribly silly of you), you’ll find that Mkay throws an exception complaining that the name of the property to validate hasn’t been set.

So we’re back on track, and we know the name of the property we’re trying to validate. Now all we have to do is to somehow transform the AST we built into .NET validation code that we can execute. To do so, we use expression trees. Expression trees allows us to programmatically build a data structure representing .NET code, and then magically transform it into executable code.

We use the venerable visitor pattern to walk the Mkay AST and build up the expression tree AST. The .NET framework offers factory methods for creating different kinds of expression nodes, such as Expression.Constant for creating a node that represents a constant value, Expression.And for the logical and operation, Expression.Add for plus and Expression.Call to represent a method call. The various methods naturally vary quite a bit with respect to what parameters they demand and the kind of expressions they return. For instance, Expression.And expects two Expression instances expected to be of type bool and returns an instance of BinaryExpression, also typed as bool. The various overloads of Expression.Call, on the other hand, return instances of MethodCallExpression and typically require a MethodInfo instance to identify the method to be called, as well as parameters to be passed to the method call. And so on and so forth. Pretty pedestrian stuff, nothing difficult.

It’s worth noting that you have to be careful and precise about types, though. For instance, the two sub-expressions passed to Expression.Add must be of the exact same type. An integer and a double cannot really be added together in a .NET program. However, if you add an integer and a double in a C# program, the compiler will make the necessary conversion for you (by turning the integer into a double). When using expression trees you need to handle such conversions manually. That is, you need to identify the type mismatch and see if you can resolve it by converting the type of one of the values into the type of the other. The general problem is known as unification in computer science and involves formulae that will make the head of the uninitiated hurt. However, Mkay takes a very simple approach by performing a lookup of available conversions for the types involved.

When expression tree has been built, we wrap things up by enveloping it in a lambda expression node of type Expression<Func<bool>>. This gives us access to a magical method called Compile. The Compile method is magical because it turns your expression tree into a validation method that can be executed. And of course that’s exactly what we do. If the state of the object is such that the validation method returns true, everything is well. Otherwise, we complain.

So as you can see, we have rock-solid server-side validation ensuring that we have short names and no suspicious deaths set in the future. We also happen to have a hard-coded earliest birth date, as well as a guarantee against zombies, but the screenshot doesn’t show that.

Now, let’s offer a superior user experience by doing the same checks client-side, as the user fills in the form. To do so, we must implement IClientValidatable, which in turn means we must implement a method called GetClientValidationRules.

public IEnumerable<ModelClientValidationRule> GetClientValidationRules(

ModelMetadata metadata, ControllerContext context)

{

var propName = metadata.PropertyName;

var builder = new JsonBuilder(propName);

var visitor = new ExpVisitor<JObject>(builder);

Tree.Accept(visitor);

var ast = visitor.GetResult();

var json = new JObject(

new JProperty("rule", _ruleSource),

new JProperty("property", propName),

new JProperty("ast", ast));

var rule = new ModelClientValidationRule

{

ErrorMessage = ErrorMessage ?? _defaultErrorMessage,

ValidationType = "mkay"

};

rule.ValidationParameters["rule"] = json.ToString();

yield return rule;

}

The string “mkay” that is set for the ValidationType is essentially a magic string that you need to match up on the JavaScript side. The same goes for the string “rule” that is used as a key for the ValidationParameters dictionary.

jQuery.validator.addMethod("mkay", function (value, element, param) {

"use strict";

var ruledata = JSON && JSON.parse(param) || $.parseJSON(param);

var validator = MKAY.getValidator(ruledata.rule, ruledata.ast);

return validator();

});

jQuery.validator.unobtrusive.adapters.add("mkay", ["rule"], function (options) {

"use strict";

options.rules.mkay = options.params.rule;

options.messages.mkay = options.message;

});

On the JavaScript side, we have to hook up our client-side validation code to the machinery that is called unobtrusive validation in jQuery. As you can see, the magic strings “mkay” and “rule” appear at various places in the code. Apart from the plumbing, nothing much happens here. A payload of JSON is picked up, deserialized, and passed to a validation function factory thing called MKAY.getValidator. That’s where the JSON AST is turned into an actual JavaScript function. First, though, let’s see an example of a JSON AST.

{

"type": "call",

"value": ">",

"operands": [

{

"type": "property",

"value": "X"

},

{

"type": "call",

"value": "+",

"operands": [

{

"type": "property",

"value": "A"

},

{

"type": "property",

"value": "B"

},

{

"type": "property",

"value": "C"

}

]

}

]

}

This example shows the JSON AST for the Mkay expression “(> X (+ A B C))”. So in other words, the rule states that the value of X should be greater than the sum of A, B and C.

As we saw earlier, the deserialized JSON is passed to a validation function factory. The transformation process is conceptually pretty simple: every node in the JSON AST becomes a function. A function may be composed from simpler functions, or it may simply return a value, such as a string or an integer. The final validation function corresponds to the root node of the AST.

Let’s look at an example. Below, you see pseudo-code for the validation function produced from the JSON AST for the Mkay expression “(> X (+ A B C))”.

function() {

return greater-than-function

(

read-property-function("."),

plus-function(

plus-function(

plus-function(

0,

read-property-function("C")),

read-property-function("B")),

read-property-function("A"))

);

}

It is pseudo-code because it shows function names that aren’t really there. I’ve included the names to make it easier to understand how functions are composed conceptually. In reality, the validation function consists exclusively of nested anonymous functions.

An important detail is that function arguments are evaluated lazily. That is, the arguments passed to functions are not values, they are themselves functions capable of returning a value. It is the responsibility of each individual function to actually call the argument functions to retrieve the argument values. Why is this? The reason is that every operation in client-side Mkay is implemented as a function, including the logical operators and and or. Since we want short-circuiting semantics for the logical operators, we only evaluate arguments as long as things go well.

function logical(fun, breaker) {

return function (args) {

var copy = args.slice(0);

while (copy.length > 0) {

var val = copy.pop()();

if (val === breaker) {

return breaker;

}

}

return !breaker;

};

}

var and = logical(function (a, b) { return a && b; }, false);

Here we see how the and function is implemented. The args parameter holds a list of functions that can be evaluated to a boolean value. We evaluate each function in turn, until we reach a function that evaluates to false or we’re done, in which case we return true.

Of course, all evaluations are postponed until we actually invoke the top-level validation function, in which case the evaluations necessary to reach a conclusion are carried out.

That’s all there is to it, really. Now we have client-side validation in Mkay. In practice, it might look like this:

And with that, we’re done. We’ll never have to write a custom validation attribute again, because Mkay is the one validation attribute to rule them all. The code is available here.

Update: Mkay is now available as a nuget package.