November 4, 2011

So-called custom HTTP handlers can be incredibly useful. It’s almost laughably easy to write your own handler, and it enables some scenarios that might be difficult, cumbersome or inelegant to support otherwise. It’s definitely something you’ll want in your repertoire if you’re an ASP.NET programmer.

In essence, what a custom HTTP handler gives you is the ability to respond to an HTTP request by creating arbitrary content on the fly and have it pushed out to the client making the request. This content could be any type of file you like. In theory it could be HTML for the browser to render, but it typically won’t be (you have regular ASP.NET pages for that, remember?). Rather, you’ll have some way of magically conjuring up some binary artefact, such as an image or a PDF document. You could take various kinds of input to your spell, such as data submitted with the request, data from a database, the phase of the moon or what have you.

I’m sure you can imagine all kinds of useful things you might do with a custom HTTP handler. On a recent project, I used it to generate a so-called bullet graph to represent the state of a project. If you use ASP.NET’s chart control, you’ll notice that it too is built around a custom HTTP handler. Any time you need a graphical representation that changes over time, you should think of writing a custom HTTP handler to do the job.

Of course, you can use custom HTTP handlers to do rather quirky things as well, just for kicks. Which brings us to the meat of this blog post.

This particular HTTP handler is inspired by the phenomenon known as Post-It War, show-casing post-it note renderings of images (often retro game characters). Unfortunately, I’m too lazy to create actual, physical post-it figures, so I figured I’d let the ASP.NET pipeline do the heavy lifting for me. I am therefore happy to present you with a custom HTTP handler to produce 8-bit-style images, using a simple JSON interface. Bet you didn’t know you needed that.

The basic idea is for the user to POST a description of the image as JSON, and have the HTTP handler turn it into an actual image. Turns out it’s really easy to do.

We’ll let the user specify the number of coarse-grained “pixels” in two dimensions, as well as the size of the “pixels”. Based on this, the HTTP handler lays out a grid constituting the image. By default, all pixels are transparent, except those that are explicitly associated with a color. For each color, we indicate coordinates for the corresponding thus-colored pixels within the grid.

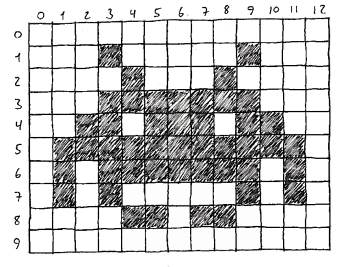

So, say we wanted to draw something simple, like the canonical space invader. We’ll draw a grid by hand, and fill in pixels as appropriate. A thirteen by ten pixel grid will do nicely.

We can glean the appropriate pixels to color black from the grid, which makes it rather easy to translate into a suitable JSON file. The result might be something like:

{

"pixelsWide": 13,

"pixelsHigh": 10,

"pixelSize": 20,

"payload":

[

{

"color" : "#000000",

"pixels" :

[

[1, 5], [1, 6], [1, 7], [2, 4],

[2, 5], [3, 1], [3, 3], [3, 4],

[3, 5], [3, 6], [3, 7], [4, 2],

[4, 3], [4, 5], [4, 6], [4, 8],

[5, 3], [5, 4], [5, 5], [5, 6],

[5, 8], [6, 3], [6, 4], [6, 5],

[6, 6], [7, 3], [7, 4], [7, 5],

[7, 6], [7, 8], [8, 2], [8, 3],

[8, 5], [8, 6], [8, 8], [9, 1],

[9, 3], [9, 4], [9, 5], [9, 6],

[9, 7], [10, 4], [10, 5],

[11, 5], [11, 6], [11, 7]

]

}

]

}

Is this the optimal textual format for describing a retro-style coarse-pixeled image? Of course not, I made it up in ten seconds (about the same time Brendan Eich spent designing and implementing JavaScript, according to Internet legend). Is it good enough for this blog post? Aaaabsolutely. But the proof of the pudding is in the eating. So let’s eat!

We’ve established that the user will be posting data like this to our custom HTTP handler; our task is to translate it into an image and feed it into the response stream. Most of this work can be done without considering the context of an HTTP handler at all. The HTTP handler is just there to expose the functionality over the web, really. It’s almost like a web service.

Unfortunately, getting the JSON from the POST request is more cumbersome than it should be. I had to reach for the request’s input stream in order to get to the data. Once you get the JSON, however, the rest is smooth sailing.

I use Json.NET‘s useful Linq-to-JSON capability to coerce the JSON into a .NET object, which I feed to the image-producing method. The Linq-to-JSON code is pretty simple, once you get used to the API:

private static PixItData ToPixItData(string json)

{

JObject o = JObject.Parse(json);

int size = o.SelectToken("pixelSize").Value<int>();

int wide = o.SelectToken("pixelsWide").Value<int>();

int high = o.SelectToken("pixelsHigh").Value<int>();

JToken bg = o.SelectToken("background");

Color? bgColor = null;

if (bg != null)

{

string bgStr = bg.Value<string>();

bgColor = ColorTranslator.FromHtml(bgStr);

}

JToken payload = o.SelectToken("payload");

var dict = new Dictionary<Color, IEnumerable<Pixel>>();

foreach (var t in payload)

{

var list = new List<Pixel>();

foreach (var xyArray in t.SelectToken("pixels"))

{

int x = xyArray[0].Value<int>();

int y = xyArray[1].Value<int>();

list.Add(new Pixel(x, y));

}

string cs = t.SelectToken("color").Value<string>();

Color clr = ColorTranslator.FromHtml(cs);

dict[clr] = list;

}

return new PixItData(wide, high, size, dict);

}

You might be able to do this even simpler by using Json.NET’s deserialization support, but this works for me. There’s a little bit of fiddling in order to allow for the optional specification of a background color for the image.

The .NET type looks like this:

public class PixItData

{

private readonly Color? _bgColor;

private readonly int _pixelsWide;

private readonly int _pixelsHigh;

private readonly int _pixelSize;

private readonly Dictionary<Color, IEnumerable<Pixel>> _data;

public PixItData(Color? bgColor, int pixelsWide,

int pixelsHigh, int pixelSize,

Dictionary<Color, IEnumerable<Pixel>> data)

{

_bgColor = bgColor;

_pixelsWide = pixelsWide;

_pixelsHigh = pixelsHigh;

_pixelSize = pixelSize;

_data = data;

}

public Color? Background

{

get { return _bgColor; }

}

public int PixelsWide

{

get { return _pixelsWide; }

}

public int PixelsHigh

{

get { return _pixelsHigh; }

}

public int PixelSize

{

get { return _pixelSize; }

}

public Dictionary<Color, IEnumerable<Pixel>> Data

{

get { return _data; }

}

}

The Pixel type simply represents an (X, Y) coordinate in the grid:

public class Pixel

{

private readonly int _x;

private readonly int _y;

public Pixel(int x, int y)

{

_x = x;

_y = y;

}

public int X

{

get { return _x; }

}

public int Y

{

get { return _y; }

}

}

Creating the image is really, really simple. We start with a blank slate that’s either transparent or has the specified background color, and then we add colored squares to it as appropriate. Here’s how I do it:

private static Image CreateImage(PixItData data)

{

int width = data.PixelSize * data.PixelsWide;

int height = data.PixelSize * data.PixelsHigh;

var image = new Bitmap(width, height);

using (Graphics g = Graphics.FromImage(image))

{

if (data.Background.HasValue)

{

Color bgColor = data.Background.Value;

using (var brush = new SolidBrush(bgColor))

{

g.FillRectangle(brush, 0, 0,

data.PixelSize * data.PixelsWide,

data.PixelSize * data.PixelsHigh);

}

}

foreach (Color color in data.Data.Keys)

{

using (var brush = new SolidBrush(color))

{

foreach (Pixel p in data.Data[color])

{

g.FillRectangle(brush,

p.X*data.PixelSize,

p.Y*data.PixelSize,

data.PixelSize,

data.PixelSize);

}

}

}

}

return image;

}

That’s just about all there is to it. The entire HTTP handler looks like this:

public class PixItHandler : IHttpHandler

{

public bool IsReusable

{

get { return true; }

}

public void ProcessRequest(HttpContext context)

{

string json = ReadJson(context.Request.InputStream);

var data = ToPixItData(json);

WriteResponse(context.Response, ToBuffer(CreateImage(data)));

}

private static PixItData ToPixItData(string json)

{

JObject o = JObject.Parse(json);

int size = o.SelectToken("pixelSize").Value<int>();

int wide = o.SelectToken("pixelsWide").Value<int>();

int high = o.SelectToken("pixelsHigh").Value<int>();

JToken bg = o.SelectToken("background");

Color? bgColor = null;

if (bg != null)

{

string bgStr = bg.Value<string>();

bgColor = ColorTranslator.FromHtml(bgStr);

}

JToken payload = o.SelectToken("payload");

var dict = new Dictionary<Color, IEnumerable<Pixel>>();

foreach (var token in payload)

{

var list = new List<Pixel>();

foreach (var xyArray in token.SelectToken("pixels"))

{

int x = xyArray[0].Value<int>();

int y = xyArray[1].Value<int>();

list.Add(new Pixel(x, y));

}

string cs = token.SelectToken("color").Value<string>();

Color clr = ColorTranslator.FromHtml(cs);

dict[clr] = list;

}

return new PixItData(wide, high, size, dict);

}

private static Image CreateImage(PixItData data)

{

int width = data.PixelSize * data.PixelsWide;

int height = data.PixelSize * data.PixelsHigh;

var image = new Bitmap(width, height);

using (Graphics g = Graphics.FromImage(image))

{

if (data.Background.HasValue)

{

Color bgColor = data.Background.Value;

using (var brush = new SolidBrush(bgColor))

{

g.FillRectangle(brush, 0, 0,

data.PixelSize * data.PixelsWide,

data.PixelSize * data.PixelsHigh);

}

}

foreach (Color color in data.Data.Keys)

{

using (var brush = new SolidBrush(color))

{

foreach (Pixel p in data.Data[color])

{

g.FillRectangle(brush,

p.X*data.PixelSize,

p.Y*data.PixelSize,

data.PixelSize,

data.PixelSize);

}

}

}

}

return image;

}

private static string ReadJson(Stream s)

{

s.Position = 0;

using (var inputStream = new StreamReader(s))

{

return inputStream.ReadToEnd();

}

}

private static byte[] ToBuffer(Image image)

{

using (var ms = new MemoryStream())

{

image.Save(ms, ImageFormat.Png);

return ms.ToArray();

}

}

private static void WriteResponse(HttpResponse response,

byte[] buffer)

{

response.ContentType = "image/png";

response.BinaryWrite(buffer);

response.Flush();

}

}

Warning: I take it for granted that you won’t put code this naïve into production, opening yourself up to denial-of-service attacks and what have you. It takes CPU and memory to produce images, you know.

Of course, as always when using a custom HTTP handler, we must add the handler to web.config. Like so:

<configuration>

<system.web>

<httpHandlers>

<add verb="POST" path="pix.it"

type="ample.code.pixit.PixItHandler, PixItHandler" />

</httpHandlers>

</system.web>

</configuration>

Note that we restrict the HTTP verb to POST, since we need the JSON data to produce the image.

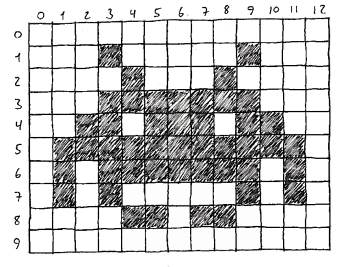

Now that we have the HTTP handler in place, we can try generating some images. A simple way to invoke the handler is to use Fiddler. Fiddler makes it very easy to build your own raw HTTP request, including a JSON payload. Just what we need. Let’s create a space invader!

All we need to do is add the appropriate headers and the JSON payload.

The image only includes the headers for the request, but Fiddler also has a text area for the request body, which is where you’ll stick the JSON data.

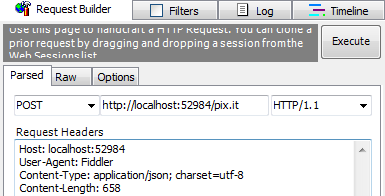

The PNG-file returned by our HTTP handler looks like this:

Nice!

Of course, we could create more elaborate images, using more pixels and more colors. For instance, the following JSON could be used to evoke the memory of a certain anti-hero named Larry, hailing from the hey-day of Sierra On-Line.

{

"background": "#54FCFC",

"pixelsWide": 18,

"pixelsHigh": 36,

"pixelSize": 4,

"payload":

[

{

"color" : "#000000",

"pixels" :

[

[2, 19],

[3, 19],

[4, 3], [4, 4], [4, 5], [4, 6], [4, 7], [4, 8], [4, 9], [4, 33],

[5, 3], [5, 4], [5, 5], [5, 6], [5, 7], [5, 8], [5, 9], [5, 33],

[6, 2], [6, 3], [6, 4], [6, 5], [6, 6], [6, 7], [6, 8], [6, 9], [6, 10], [6, 11], [6, 33],

[7, 2], [7, 3], [7, 4], [7, 5], [7, 6], [7, 7], [7, 8], [7, 9], [7, 10], [7, 11], [7, 33],

[8, 2], [8, 3], [8, 4], [8, 5], [8, 6], [8, 12],

[9, 2], [9, 3], [9, 4], [9, 5], [9, 6], [9, 12],

[10, 2], [10, 3], [10, 12], [10, 13], [10, 14], [10, 15], [10, 18], [10, 19], [10, 20], [10, 21],

[11, 2], [11, 3], [11, 12], [11, 13], [11, 14], [11, 15], [11, 18], [11, 19], [11, 20], [11, 21],

[12, 3], [12, 5], [12, 33],

[13, 3], [13, 5], [13, 33],

[14, 33],

[15, 33]

]

},

{

"color" : "#A8A8A8",

"pixels" :

[

[2, 15], [2, 16], [2, 17], [2, 18],

[3, 15], [3, 16], [3, 17], [3, 18],

[4, 14], [4, 15], [4, 16],

[5, 14], [5, 15], [5, 16],

[6, 15], [6, 16], [6, 17],

[7, 15], [7, 16], [7, 17],

[8, 18], [8, 24],

[9, 18], [9, 24],

[10, 22], [10, 23], [10, 24],

[11, 22], [11, 23], [11, 24]

]

},

{

"color" : "#FFFFFF",

"pixels" :

[

[4, 30], [4, 31], [4, 32],

[5, 30], [5, 31], [5, 32],

[6, 12], [6, 13], [6, 14], [6, 18], [6, 19], [6, 20], [6, 21], [6, 22], [6, 23], [6, 27], [6, 28], [6, 29], [6, 30],

[7, 12], [7, 13], [7, 14], [7, 18], [7, 19], [7, 20], [7, 21], [7, 22], [7, 23], [7, 27], [7, 28], [7, 29], [7, 30],

[8, 13], [8, 14], [8, 15], [8, 16], [8, 17], [8, 19], [8, 20], [8, 21], [8, 22], [8, 23], [8, 25], [8, 26], [8, 27],

[9, 13], [9, 14], [9, 15], [9, 16], [9, 17], [9, 19], [9, 20], [9, 21], [9, 22], [9, 23], [9, 25], [9, 26], [9, 27],

[10, 16], [10, 17],

[11, 16], [11, 17],

[12, 16], [12, 17], [12, 24], [12, 25], [12, 26], [12, 27], [12, 28], [12, 29], [12, 30], [12, 31], [12, 32],

[13, 16], [13, 17], [13, 24], [13, 25], [13, 26], [13, 27], [13, 28], [13, 29], [13, 30], [13, 31], [13, 32]

]

},

{

"color" : "#FC5454",

"pixels" :

[

[4, 19], [4, 20],

[5, 19], [5, 20],

[8, 8], [8, 9], [8, 10], [8, 11],

[9, 8], [9, 9], [9, 10], [9, 11],

[10, 5], [10, 6], [10, 7], [10, 8], [10, 9], [10, 10],

[11, 5], [11, 6], [11, 7], [11, 8], [11, 9], [11, 10],

[12, 6], [12, 7], [12, 8], [12, 9],

[13, 6], [13, 7], [13, 8], [13, 9],

[14, 6], [14, 7], [14, 16], [14, 17],

[15, 6], [15, 7], [15, 16], [15, 17]

]

},

{

"color" : "#A80000",

"pixels" :

[

[8, 7],

[9, 7],

[10, 4], [11, 4], [12, 4], [13, 4]

]

}

]

}

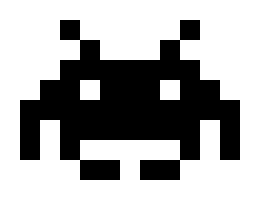

The result?

You might say “that’s a big file to create a small image”, but that would be neglecting the greatness of the Laffer, and his impact on a generation of young adolescents.