October 5, 2011

Iterators, man. They’re so much fun.

I’ve messed about with IEnumerable<T> a little bit before, even in the short history of this blog, but I don’t feel like I can say I’ve done so in anger. Sort of the litmus test to see if you’ve grokked lazy evaluation is to implement an infinite sequence of some sort, wouldn’t you agree? Until you do that it’s all talk and no walk. So I thought I’d rectify that, to be a certified IEnumerable<T>-grokker. You in?

We’ll start gently. The simplest example of an infinite sequence that I can think of is this:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5…

You’re absolutely right, it’s the sequence of positive integers!

There are actually two simple ways to implement an IEnumerable<int> that would give you that. First off, you could write the dynamic duo of IEnumerable<int> and IEnumerator<int> that conspire to let you write code using the beloved foreach keyword. As you well know, foreach over an IEnumerable<T> compiles to IL that will obtain an IEnumerator<T> and use that to do the actual iteration. (I was going to write iterate over here, but that sort of presupposes that you’ve got something finite that you’re stepping through, doesn’t it?)

Anyways, first implementation:

public class Incrementer : IEnumerable<int>

{

public IEnumerator<int> GetEnumerator()

{

return new IncrementingEnumerator();

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

public class IncrementingEnumerator : IEnumerator<int>

{

private int _n;

public bool MoveNext()

{

++_n;

return true;

}

public int Current

{

get { return _n; }

}

object IEnumerator.Current

{

get { return Current; }

}

public void Dispose() { }

public void Reset()

{

_n = 0;

}

}

An alternative implementation would be this:

public class ContinuationIncrementer : IEnumerable<int>

{

public IEnumerator<int> GetEnumerator()

{

int n = 0;

while (true)

{

yield return ++n;

}

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

This is simpler in terms of lines of code, but it requires you to understand what the yield keyword does. So what does the yield keyword do? Conceptually, yield gives you what is known as a continuation. In essence, it allows you to jump right back into the code where you left off at the previous step in the iteration. Of course, the best way to find out what is going on under the hood is to look at the IL. If you do that, you’ll see that what the C# compiler actually does is conjure up an IEnumerator<int> of its own. This generated class essentially performs the same task as our handwritten IncrementingEnumerator.

Unsurprisingly, then, the end result is the same, regardless of the implementation we choose. What Incrementer gives you is an infinite sequence of consecutive positive integers, starting with 1. So if you have code like this:

foreach (int i in new Incrementer())

{

Console.WriteLine(i);

if (i == 10) { break; }

}

That’s going to print the numbers 1 through 10. And since there’s no built-in way to stop the Incrementer, it’s fairly important to break out of that loop!

That’s not terribly interesting, though. Although it might be worth noting that at least it consumes little memory, since the IEnumerable<int> only holds on to a single integer at a time. That’s good. Furthermore, we could generalize it to produce the sequence

n, 2n, 3n, 4n, 5n…

instead (without exciting people too much, I guess). We could even provide an additional constructor to enable you to set a start value k, so you’d get the sequence

n+k, 2n+k, 3n+k, 4n+k, 5n+k…

Still not excited? Oh well. There’s no pleasing some people.

Let’s implement it anyway. We’ll call it NumberSequence and have it use a NumberEnumerator to do the actual work, such as it is (it isn’t much):

public class NumberSequence : IEnumerable<int>

{

private readonly int _startValue;

private readonly int _increment;

public NumberSequence(int startValue, int increment)

{

_startValue = startValue;

_increment = increment;

}

public IEnumerator<int> GetEnumerator()

{

return new NumberEnumerator(_startValue, _increment);

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

public class NumberEnumerator : IEnumerator<int>,

IComparable<NumberEnumerator>

{

private readonly int _increment;

private int _currentValue;

public NumberEnumerator(int startValue, int increment)

{

_currentValue = startValue;

_increment = increment;

}

public bool MoveNext()

{

_currentValue += _increment;

return true;

}

public int Current

{

get { return _currentValue; }

}

object IEnumerator.Current

{

get { return Current; }

}

public void Dispose() { }

public void Reset()

{

throw new NotSupportedException();

}

public int CompareTo(NumberEnumerator other)

{

return Current.CompareTo(other.Current);

}

}

You’ll notice that I got a bit carried away and implemented IComparable<NumberEnumerator> as well, so that we could compare the state of two such NumberEnumerator instances should we so desire.

A completely different, but equally simple way to create an infinite sequence is to repeat the same finite sequence over and over again. You could do that completely generically, by repeating an IEnumerable<T>. Like so:

public class BrokenRecord<T> : IEnumerable<T>

{

private readonly IEnumerable<T> _seq;

public BrokenRecord(IEnumerable<T> seq)

{

_seq = seq;

}

public IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator()

{

var e = _seq.GetEnumerator();

return new BrokenRecordEnumerator<T>(e);

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

public class BrokenRecordEnumerator<T> : IEnumerator<T>

{

private readonly IEnumerator<T> _seq;

public BrokenRecordEnumerator(IEnumerator<T> seq)

{

_seq = seq;

}

public void Dispose() {}

private bool ResetAndMoveNext()

{

Reset();

return _seq.MoveNext();

}

public bool MoveNext()

{

return _seq.MoveNext() || ResetAndMoveNext();

}

public void Reset()

{

_seq.Reset();

}

public T Current

{

get

{

return _seq.Current;

}

}

object IEnumerator.Current

{

get { return Current; }

}

}

So you could write code like this:

var words = new [] { "Hello", "dear", "friend" };

int wordCount = 0;

foreach (string s in new BrokenRecord(words))

{

Console.WriteLine(s);

if (++wordCount == 10) { break; }

}

And of course the output would be:

Hello

dear

friend

Hello

dear

friend

Hello

dear

friend

Hello

Now you could put a finite sequence of numbers in there, or just about any sequence you like, in fact. Including, as it were, an infinite sequence of some sort - although that wouldn’t be very meaningful, since you’d never see that thing starting over!

So yeah, we’re starting to see how we can create infinite sequences, and it’s all very easy to do. But what can you do with it?

Let’s turn our attention to an archetypical academic exercise: generating a sequence of prime numbers. Now as you well know, prime numbers aren’t as useless as they might seem to the untrained eye - there are practical applications in cryptography and what have you. But we’re not interested in that right now; we’re going for pure academic interest here. Let’s not fool ourselves to think we’re doing anything useful.

A well-known technique for finding prime numbers is called the Sieve of Eratosthenes (a sieve being a device that separates wanted elements from unwanted ones). In a nutshell, the Sieve of Eratosthenes works like this:

You have a finite list of consecutive integers, starting at 2. You take the first number in the list and identify it as a prime. Then you go over the rest of the list, crossing out any multiples of that prime (since obviously multiples of a prime cannot be other primes). Then you take the next number in the list that hasn’t been crossed out. That’s also a prime, so you repeat the crossing out process for that prime. And so on and so forth until you’re done.

Here’s a simple example of the primes from 2-20.

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

The number 2 is a prime! Cross out all the multiples of 2.

2 3 X 5 X 7 X 9 X 11 X 13 X 15 X 17 X 19 X

The number 3 is also a prime! Now cross out all its multiples:

2 3 X 5 X 7 X X X 11 X 13 X X X 17 X 19 X

And we keep going for 5, 7, 11, 13, 17 and 19. As it turns out, all the multiples have already been covered by other prime-multiples, so there are actually no more numbers being crossed out. But algorithmically, we obviously need to go through the same process for all the primes.

Now, a problem with the Sieve of Eratosthenes as it is formulated here, is that it presupposes a finite list of numbers, and hence you get a finite list of primes as well. We want an infinite list, otherwise surely we won’t certify as IEnumerable<T>-grokkers. Luckily, it is possible to adjust the Sieve of Eratosthenes to cope with infinite lists of numbers. There’s a very readable paper by Melissa O’Neill that shows how you could go about it. The trick is to do just-in-time elimination of prime-multiples, instead of carrying out the elimination immediately when the prime is found.

Essentially, we maintain an infinite sequence of prime-multiples for each prime we encounter. For each new number we want to check, we check to see if there are pending prime-multiples (i.e. obvious non-primes) matching the number. If there are, the number is not a prime (since we’re looking at a number that would have been eliminated in the finite Sieve of Erastosthenes). The number is discarded just-in-time, and the eliminating sequence(s) of prime-multiples are advanced to the next prime-multiple. If there is no matching prime-multiple in any of the sequences, the number is a brand new prime. This means that we need to add a new infinite sequence of prime-multiples to our collection. In other words, we’re aggregating such sequences as we go along. Luckily, they each hold on to no more than a single integer value (See, I told you that was useful. And you wouldn’t believe me!)

Now how do we keep track of our prime-multiple-sequences? A naive approach would be to keep them all in a list, and just check them all for each candidate number. That wouldn’t be too bad for a small number of primes. However, say you’re looking to see if a number n is the 1001th prime - you’d have to go through all 1000 prime-multiple sequences to see if any of them eliminate n as a candidate. That’s a lot of unnecessary work! What we really need to do, is check the one(s) with the smallest pending prime-multiple. Using a priority queue to hold our sequences makes this an O(1) operation. Unfortunately, the .NET framework doesn’t contain an implementation of a priority queue. Fortunately, the C5 Generic Collection Library does. So we’ll use that.

Here, then, is how we could implement an IEnumerable<int> that represents an infinite sequence of primes:

public class PrimeSequence : IEnumerable<int>

{

public IEnumerator<int> GetEnumerator()

{

return new SimplePrimeEnumerator();

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

public class SimplePrimeEnumerator : IEnumerator<int>

{

private readonly IEnumerator<int> _candidates =

new NumberSequence(1, 1).GetEnumerator();

private IPriorityQueue<NumberEnumerator> _pq =

new IntervalHeap<NumberEnumerator>();

public int Current

{

get { return _candidates.Current; }

}

public bool MoveNext()

{

while (true)

{

_candidates.MoveNext();

int n = _candidates.Current;

if (_pq.IsEmpty || n < _pq.FindMin().Current)

{

// There are no pending prime-multiples.

// This means n is a prime!

_pq.Add(new NumberEnumerator(n*n, n));

return true;

}

do

{

var temp = _pq.DeleteMin();

temp.MoveNext();

_pq.Add(temp);

} while (n == _pq.FindMin().Current);

}

}

object IEnumerator.Current

{

get { return Current; }

}

public void Reset()

{

throw new NotSupportedException();

}

public void Dispose() {}

}

An interesting thing to point out is that the prime-multiple sequence doesn’t have to start until prime*prime. Why? Because smaller multiples of the prime will already be covered by previously considered primes! For instance, the prime-multiple sequence for 17 doesn’t have to contain the multiple 17*11 since the prime-multiple sequence for 11 will contain the same number.

Now this implementation is actually pretty decent. There’s just one thing that leaps to mind as sort of wasted effort. We’re checking every number there is to see if it could possibly be a prime. Yet we know that 2 is the only even number that is a prime (all the others, well, they’d be divisible by 2, right?). So half of our checks are completely in vain.

What if we baked in a little bit of smarts to handle this special case? Say we create a PrimeSequence like so:

public class PrimeSequence : IEnumerable<int>

{

public IEnumerator<int> GetEnumerator()

{

yield return 2;

var e = new OddPrimeEnumerator();

while (e.MoveNext())

{

yield return e.Current;

}

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

The OddPrimeEnumerator is actually quite similar to the naive PrimeEnumerator, except three things:

public class OddPrimeEnumerator : IEnumerator<int>

{

private readonly IEnumerator<int> _candidates =

new NumberEnumerator(3, 2);

private readonly IPriorityQueue<NumberEnumerator> _pq =

new IntervalHeap<NumberEnumerator>();

public int Current

{

get { return _candidates.Current; }

}

public bool MoveNext()

{

while (true)

{

_candidates.MoveNext();

int n = _candidates.Current;

bool crossedOut = false;

while (!crossedOut)

{

if (_pq.IsEmpty || n < _pq.FindMin().Current)

{

// There are no pending prime-multiples.

// This means n is a prime!

_pq.Add(new NumberEnumerator(n * n, n));

return true;

}

crossedOut = n == _pq.FindMin().Current;

do

{

var temp = _pq.DeleteMin();

temp.MoveNext();

_pq.Add(temp);

} while ((n > _pq.FindMin().Current) ||

(crossedOut && n == _pq.FindMin().Current));

}

}

}

object IEnumerator.Current

{

get { return Current; }

}

public void Dispose() { }

public void Reset()

{

throw new NotSupportedException();

}

}

Note that we must go out of our way a little bit to handle the case where we skip past a prime-multiple. Hence the code is microscopically uglier, but we cut our work pretty much in half. But of course, it’s tempting to go further. We check an awful lot of multiples of 3 as well, you know? And of 5? What if we could just skip those too? Turns out there’s a well-known optimization technique known as “wheel factorization” that allows us to do just that.

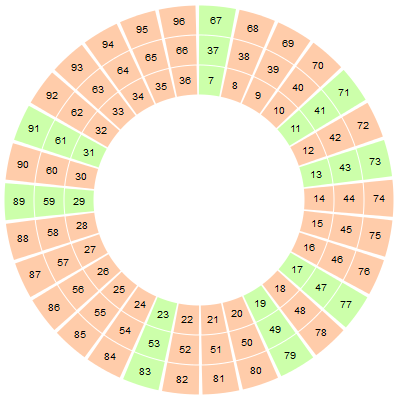

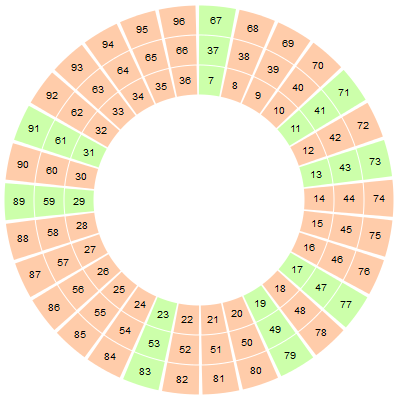

Here’s a 2*3*5 wheel (well, the three first layers of it, anyway). Note that it starts at 7, which is the first prime we’re not including in this wheel factorization.

The green “spokes” of the wheel represents sectors where you might find a prime number. The big red areas you don’t even have to check, because they contain only multiples of the first three primes.

Obviously then, the wheel allows us to rule out a great deal of numbers right off the bat. The numbers not filtered out by the wheel are checked in the normal way. According to O’Neill, there are quickly diminishing returns in using large wheels, so we’ll restrain ourselves to a small wheel that takes out the multiples of 2, 3, and 5.

Now how do we implement this wheel in our code? Well, clearly the wheel can be represented as another infinite sequence, with the characteristic that it repeats the same pattern of numbers to skip over and over again. Well gee, that sounds almost like a broken record, doesn’t it? (You’d think I planned these things!)

Say you wanted to create an infinite skip sequence corresponding to the wheel shown above. This code would do nicely:

var skip = new[] { 4, 2, 4, 2, 4, 6, 2, 6 };

var skipSequence = new BrokenRecord<int>(skip);

Now we can use the skip sequence to create a sequence of prime candidate numbers. We’ll call it a WheelSequence for lack of a better term.

public class WheelSequence : IEnumerable<int>

{

private readonly int _startValue;

private readonly IEnumerable<int> _;

public WheelSequence(int startValue,

IEnumerable<int> skipSequence)

{

_startValue = startValue;

_ = skipSequence;

}

public IEnumerator<int> GetEnumerator()

{

yield return _startValue;

var wse = new WheelSequenceEnumerator(_startValue,

_.GetEnumerator());

while (wse.MoveNext())

{

yield return wse.Current;

}

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

public class WheelSequenceEnumerator : IEnumerator<int>

{

private readonly IEnumerator<int> _;

private int _value;

public WheelSequenceEnumerator(int startValue,

IEnumerator<int> skip)

{

_value = startValue;

_ = skip;

}

public bool MoveNext()

{

_.MoveNext();

_value += _.Current;

return true;

}

public int Current

{

get { return _value; }

}

object IEnumerator.Current

{

get { return Current; }

}

public void Reset()

{

throw new NotSupportedException();

}

public void Dispose() { }

}

Now we can replace our original naive PrimeEnumerator with one that uses wheel factorization to greatly reduce the number of candidates considered.

public class WheelPrimeEnumerator : IEnumerator<int>

{

private readonly IEnumerator<int> _candidates =

new WheelSequence(11,

new BrokenRecord<int>(

new[] { 4, 2, 4, 2, 4, 6, 2, 6 }

)

).GetEnumerator();

private readonly IPriorityQueue<NumberEnumerator> _pq =

new IntervalHeap<NumberEnumerator>();

public int Current

{

get { return _candidates.Current; }

}

public bool MoveNext()

{

while (true)

{

_candidates.MoveNext();

int n = _candidates.Current;

bool crossedOut = false;

while (!crossedOut)

{

if (_pq.IsEmpty || n < _pq.FindMin().Current)

{

// There are no pending prime-multiples.

// This means n is a prime!

_pq.Add(new NumberEnumerator(n*n, n));

return true;

}

crossedOut = n == _pq.FindMin().Current;

do

{

var temp = _pq.DeleteMin();

temp.MoveNext();

_pq.Add(temp);

} while ((n > _pq.FindMin().Current) ||

(crossedOut && n == _pq.FindMin().Current));

}

}

}

object IEnumerator.Current

{

get { return Current; }

}

public void Dispose() {}

public void Reset()

{

throw new NotSupportedException();

}

}

This particular implementation uses a wheel that pre-eliminates multiples of 2, 3, and 5, but obviously you could use any wheel you want. Note that the only difference between this implementation and the OddPrimeEnumerator is in the choice of IEnumerator<int> for prime number candidates. The rest is unchanged.

Of course, to use this thing, we must first manually yield the primes that we eliminated the multiples of. Like so:

public class WheelPrimeSequence : IEnumerable<int>

{

public IEnumerator<int> GetEnumerator()

{

yield return 2;

yield return 3;

yield return 5;

var e = new WheelPrimeEnumerator();

while (e.MoveNext())

{

yield return e.Current;

}

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

That just about wraps it up. I should point out that the current implementation doesn’t really give you an infinite sequence of primes. Unfortunately, the abstraction is all a-leak like a broken faucet since the pesky real world of finite-sized integers causes it to break down at a certain point. In fact, for the current implementation, that point is after the 4.792th prime, which is 46.349. Why? Because then we start a prime-multiple sequence at 46.349*46.349, which won’t fit into the 32-bit integer we’re currently using to store the current value. Hence we get a overflow, the prime-multiple sequence gets a negative number, and it’s all messed up. We really should put an if-statement in there, to return false from MoveNext if and when we overflow, effectively terminating our not-so-infinite-infinite sequence.

Of course we could use a 64-bit integer instead, but keep in mind that we’re really just buying time - we’re not fixing the underlying problem. C# doesn’t have arbitrary-sized integers, end of story. Nevertheless, 64-bit integers will give you primes larger than 3.000.000.000. I’d say it’s good enough for an academic exercise; or as I like to put it, large enough for all impractical purposes.

Do I certify?