May 12, 2011

The using statement in C# is a peculiar spoonful of syntactic sugar. It is peculiar because it’s tailor-made for a particular interface in the .NET framework. (i.e. IDisposable). Hence in the C# standard, you’ll find that the semantics of using is defined in terms of how it interacts with that interface, the existence of which is sort of assumed a priori. So the boundary between language and library gets really blurred.

As you well know, the purpose of using is to make it 1) more convenient for programmers to work with so-called unmanaged resources, and 2) more likely that programmers will dispose of such resources in a timely manner. That’s why it’s there.

The archetypical usage is something like:

using (var resource = new Resource())

{

// Use the resource here.

}

This will expand to:

var resource = new Resource();

try

{

// Use the resource here.

}

finally {

if (resource != null)

{

resource.Dispose();

}

}

The using statement has a lot of potential use cases beyond that, though - indeed, that’s what this blog post is all about! The MSDN documentation states that “the primary use of IDisposable is to release unmanaged resources”, but it is easy and fun to come up with interesting secondary uses. Basically any time you need something to happen before and after an operation, you got a potential use case for using. In other words, you can use it as sort of a poor man’s AOP.

Some people find the secondary uses for using to be abuse, others find it artistic. The most convincing argument I’ve read against liberal use of using is Eric Lippert’s comment on this stack overflow question. Essentially, the argument is that a Dispose method should be called out of politeness, not necessity: the correctness of your code shouldn’t depend upon Dispose being called. I won’t let that stop me though! (Granted, you’d need to put 1024 me’s in a cluster to get the brain equivalent of a Lippert, but hey - he’s just this guy, you know?). After all, what does code correctness mean? If your application leaks scarce resources due to untimely disposal, it’s broken - you’ll find it necessary to explicitly dispose of them. There’s a sliding scale between politeness and necessity, between art and abuse, and it’s not always obvious when you’re crossing the line. Also, I have to admit, I have a soft spot for cute solutions, especially when it makes for clean, readable code. I therefore lean towards the forgiving side. YMMW.

So with that out of the way, let’s start abusing using:

In my mind, the simplest non-standard application of using is to measure the time spent doing some operation (typically a method call). A PerfTimer implementing IDisposible gives you a neat syntax for that:

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

using (new PerfTimer())

{

// Do your thing.

}

}

}

class PerfTimer : IDisposable

{

private readonly Stopwatch _ = new Stopwatch();

public PerfTimer()

{

_.Start();

}

public void Dispose()

{

_.Stop();

Console.WriteLine("Spent {0} ms.", _.ElapsedMilliseconds);

}

}

Note that you don’t have to hold on to the PerfTimer you obtain in the using statement, since you’re not actually using it inside the scope of the using block. Obviously Dispose will be called nevertheless.

Impersonation is one of my favorite using use cases. What you want is to carry out a sequence of instructions using a particular identity, and then revert to the original identity when you’re done. Wrapping your fake id up in an IDisposable makes it all very clean and readable:

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

WindowsIdentity id = …;

using (new Persona(id))

{

// Act as id.

}

}

}

class Persona : IDisposable

{

private readonly WindowsImpersonationContext _;

public Persona(WindowsIdentity id)

{

_ = id.Impersonate();

}

public void Dispose()

{

_.Undo();

}

}

Another useful application of using is to fake out some global resource during testing. It’s really a kind of dependency injection happening in the using statement. The neat thing is that you can reinject the real object when you’re done. This can help avoid side-effects from one test affecting another test.

Let’s say you want to control time:

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

Tick(); Tick(); Tick();

DateTime dt = DateTime.Now;

using (Timepiece.Replacement(() => dt.Add(dt - DateTime.Now)))

{

Tick(); Tick(); Tick();

}

Tick(); Tick(); Tick();

}

static void Tick()

{

Thread.Sleep(1000);

Console.WriteLine("The time is {0}", Timepiece.Now.ToLongTimeString());

}

}

public static class Timepiece

{

private static Func<DateTime> _ = () => DateTime.Now;

public static DateTime Now { get { return _(); } }

public static IDisposable Replacement(Func<DateTime> f)

{

return new TempTimepiece(f);

}

class TempTimepiece : IDisposable

{

private readonly Func<DateTime> _original;

public TempTimepiece(Func<DateTime> f)

{

_original = _;

_ = f;

}

public void Dispose()

{

_ = _original;

}

}

}

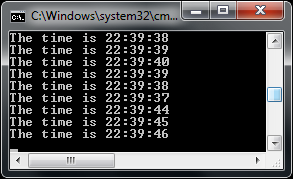

The idea is that we eliminate uses of DateTime.Now in our code, and consistently use Timepiece.Now instead. By default, Timepiece.Now uses DateTime.Now to yield the current time, but you’re free to replace it. You can pass in your own time provider to the Replacement method, and that we be used instead - until someone calls Dispose on the TempTimepiece instance returned from Replacement, that is. In the code above, we’re causing time to go backwards for the three Ticks inside the using block. The output looks like this:

So far we’ve seen some modest examples of abuse. For our last example, let’s go a bit overboard, forget our inhibitions and really embrace using!

Here’s what I mean:

public override void Write()

{

using(Html())

{

using (Head())

{

using (Title())

{

Text("Greeting");

}

}

using (Body(Bgcolor("pink")))

{

using(P(Style("font-size:large")))

{

Text("Hello world!");

}

}

}

}

Hee hee.

Yup, it’s an embedded DSL for writing HTML, based on the using statement. Whatever your other reactions might be - it’s fairly readable, don’t you think?

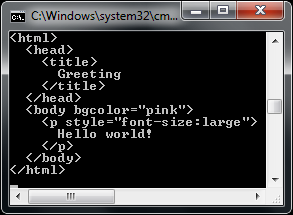

When you run it, it produces the following output (nicely formatted and everything):

How does it work, though?

Well, the basic idea is that you don’t really have to obtain a new IDisposable every time you’re using using. You can keep using the same one over and over, altering its state as you go along. Here’s how you can do it:

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

new HtmlWriter(Console.Out).Write();

}

}

class HtmlWriter : BaseHtmlWriter

{

public HtmlWriter(TextWriter tw) : base(tw) {}

public override void Write()

{

using(Html())

{

using (Head())

{

using (Title())

{

Text("Greeting");

}

}

using (Body(Bgcolor("pink")))

{

using(P(Style("font-size:large")))

{

Text("Hello world!");

}

}

}

}

}

class DisposableWriter : IDisposable

{

private readonly Stack<string> _tags = new Stack<string>();

private readonly TextWriter _;

public DisposableWriter(TextWriter tw)

{

_ = tw;

}

public IDisposable Tag(string tag, params string[] attrs)

{

string s = attrs.Length > 0 ? tag + " " + string.Join(" ", attrs) : tag;

Write("<" + s + ">");

_tags.Push(tag);

return this;

}

public void Text(string s)

{

Write(s);

}

private void Write(string s) {

_.WriteLine();

}

public void Dispose()

{

var tag = _tags.Pop();

Write("</" + tag + ">");

}

}

abstract class BaseHtmlWriter

{

private readonly DisposableWriter _;

protected BaseHtmlWriter(TextWriter tw)

{

_ = new DisposableWriter(tw);

}

protected IDisposable Html()

{

return _.Tag("html");

}

protected IDisposable Body(params string[] attrs)

{

return _.Tag("body", attrs);

}

// More tags…

protected string Bgcolor(string value)

{

return Attr("bgcolor", value);

}

protected string Style(string value)

{

return Attr("style", value);

}

// More attributes…

protected string Attr(string key, string value)

{

return key + "=\"" + value + "\"";

}

protected void Text(string s)

{

_.Text(s);

}

public abstract void Write();

}

So you can see, it’s almost like you’re using an IDisposable in a fluent interface. You just keep using the same DisposableWriter over and over again! Internally, it maintains a stack of tags. Whenever you add a new tag to the writer (which happens on each new using), it writes the start tag to the stream and pushes it onto the stack. When the using block ends, Dispose is called on the DisposableWriter - causing it to pop the correct tag off the stack and write the corresponding end tag to the stream. The indentation is determined by the depth of the stack, of course.

Wasn’t that fun? There are other things you could do, too. For instance, I bet you could implement an interpreter for a stack-based language (such as IL) pretty easily. Let each instruction implement IDisposable, pop values off the stack upon instantiation, execute the instruction, optionally push a value back on upon Dispose. Shouldn’t be hard at all.

Now if I could only come up with some neat abuses of foreach…