April 28, 2011

In the last post, we saw that data binding in ASP.NET doesn’t support polymorphism. We also saw that we could mitigate the problem by using simple wrapper types. Writing such wrappers by hand won’t kill you, but it is fairly brain-dead. I mentioned that an alternative would be to generate the wrappers at runtime, using reflection. That actually sounds like a bit of fun, so let’s see how it can be done. If nothing else, it’s a nice introductory lesson in using Reflection.Emit.

As an example, let’s revisit our two four-legged friends and one enemy from the previous post: the Dog, the Chihuahua and the Wolf. They all implement ICanine.

The canines have gained a skill since last time, though - they can now indicate whether or not they’ll enjoy a particular kind of food. The code looks like this:

public enum Food { Biscuit, Meatballs, You }

public interface ICanine

{

string Bark { get; }

bool Eats(Food f);

}

public class Wolf : ICanine

{

public virtual string Bark { get { return "Aooo!"; } }

public bool Eats(Food f) { return f != Food.Biscuit; }

}

public class Dog : ICanine

{

public virtual string Bark { get { return "Woof!"; } }

public virtual bool Eats(Food f) { return f != Food.You; }

}

public class Chihuahua : Dog

{

public override string Bark { get { return "Arff!"; } }

public override bool Eats(Food f) { return f == Food.Biscuit; }

}

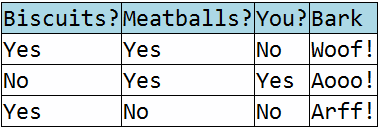

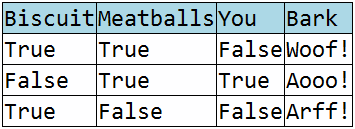

What we want to do in our web application is display a grid that shows the canine’s eating preferences as well as its bark. This calls for a combination of auto-generated and custom columns: an automatic one for the Bark property, and a custom one for each kind of food.

The DataGrid is declared in the .aspx page:

<asp:DataGrid

ID="_grid"

runat="server"

Auto-generateColumns="true"

Font-Size="X-Large"

Font-Names="Consolas"

HeaderStyle-BackColor="LightBlue" />

This gives us a column for the Bark out of the box.

In the code-behind, we add a column for each kind of food. We also get a list of canines, which we wrap in something called an BoxEnumerable<ICanine> before binding to it.

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

GetGridColumns().ForEach(f => _grid.Columns.Add(f));

_grid.DataSource = new BoxEnumerable<ICanine>(GetCanines());

_grid.DataBind();

}

private static List<DataGridColumn> GetGridColumns()

{

return new List<DataGridColumn>

{

new TemplateColumn

{

HeaderText = "Biscuits?",

ItemTemplate = new FoodColumnTemplate(Food.Biscuit)

},

new TemplateColumn

{

HeaderText = "Meatballs?",

ItemTemplate = new FoodColumnTemplate(Food.Meatballs)

},

new TemplateColumn

{

HeaderText = "You?",

ItemTemplate = new FoodColumnTemplate(Food.You)

}

};

}

private static IEnumerable<ICanine> GetCanines()

{

return new List<ICanine> {new Dog(), new Wolf(), new Chihuahua() };

}

The food preference columns use an ItemTemplate called FoodColumnTemplate. It’s a simple example of data binding which goes beyond mere properties, since we’re invoking a method on the data item:

class FoodColumnTemplate : ITemplate

{

private readonly Food _food;

public FoodColumnTemplate(Food food)

{

_food = food;

}

public void InstantiateIn(Control container)

{

var label = new Label();

label.DataBinding += OnDataBinding;

container.Controls.Add(label);

}

private void OnDataBinding(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

var label = (Label) sender;

var row = (DataGridItem) label.NamingContainer;

var canine = (ICanine) row.DataItem;

label.Text = canine.Eats(_food) ? "Yes" : "No";

}

}

If we run the application, we get the result we wanted:

Without the presence of the BoxEnumerable<ICanine> above, though, we’d have a runtime exception at our hands. Under the covers, BoxEnumerable<ICanine> is producing the necessary wrappers around the actual canines to keep the DataGrid happy.

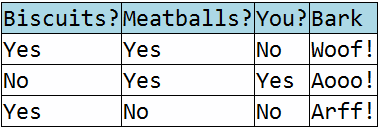

Let’s see how we can do this. Here’s an overview of the different moving parts:

That’s a fair amount of types, but most of them have trivial implementations. Consider BoxEnumerable<T> first:

public class BoxEnumerable<T> : IEnumerable<Box<T>>

{

private readonly IEnumerable<T> _;

public BoxEnumerable(IEnumerable<T> e)

{

_ = e;

}

public IEnumerator<Box<T>> GetEnumerator()

{

return new BoxEnumerator<T>(_.GetEnumerator());

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator()

{

return GetEnumerator();

}

}

As you can see, it’s really the simplest possible wrapper around the original IEnumerable<T>, turning it into an IEnumerable<Box<T>>. It relies on another wrapper type, BoxEnumerator<T>:

public class BoxEnumerator<T> : IEnumerator<Box<T>>

{

private readonly IEnumerator<T> _;

private readonly BoxFactory<T> _factory = new BoxFactory<T>();

public BoxEnumerator(IEnumerator<T> e)

{

_ = e;

}

public void Dispose()

{

_.Dispose();

}

public bool MoveNext()

{

return _.MoveNext();

}

public void Reset()

{

_.Reset();

}

public Box<T> Current

{

get { return _factory.Get(_.Current); }

}

object IEnumerator.Current

{

get { return Current; }

}

}

That too is just a minimal wrapper. The only remotely interesting code is in the Current property, where a BoxFactory<T> is responsible for turning the T instance into a Box<T> instance. BoxFactory<T> looks like this:

public class BoxFactory<T>

{

private readonly Box<T> _ = EmptyBoxFactory.Instance.CreateEmptyBox<T>();

public Box<T> Get(T t)

{

return _.Create(t);

}

}

This is short but a little weird, perhaps. For fun, we’re adding a dash of premature optimization here. We’re using EmptyBoxFactory to create an “empty” instance of Box<T> (that is, without an instance of T inside). The BoxFactory<T> holds on to that empty instance for the rest of its lifetime, and uses it to create “populated” boxes. In other words, the initial empty box acts as a prototype for all subsequent boxes. That way, we avoid using reflection more than once to create the boxes. This should make people who fear the performance penalty of reflection a little happier. Let’s see how the prototype creates populated boxes for the factory:

public Box<T> Create(T t)

{

var box = (Box<T>) MemberwiseClone();

box._ = t;

return box;

}

Easy as pie, we’re just cloning and setting the protected T field. Doesn’t get much simpler than that.

It’s time to start worrying about the box itself, though. Of course, this is where things get both non-trivial and interesting.

So the goal is to create a type at runtime. The type should be used to wrap each item in an IEnumerable<T>, so that the control’s DataSource is set to a perfectly homogenous IEnumerable. That is, it will only contain instances of the same concrete type. The wrapper type won’t have any intelligence of its own, it will merely delegate to the wrapped instance of T.

To support auto-generation of columns, the wrapper type must have the same public properties as T. (We won’t consider the option of masking or renaming properties - that’s a use case that goes beyond just fixing what is broken.) In the case of T being an interface, a viable option would be for the wrapper type to implement T. However, we need the wrapper to work for all kinds of T, including when T is a base class with one or more non-virtual members. In the general case, therefore, the wrapper must simply mimic the same properties, duck typing-style.

Auto-generation of columns is pretty nifty, and a property-mimicking wrapper is sufficient for that scenario. For more sophisticated data binding scenarios, though, you need to be able to call arbitrary methods on the item we’re binding to. To do so in the general case (where T might be a class), we need some way of shedding the wrapper. We can’t simply call the methods on the wrapper itself, since we don’t have access to the name of the dynamically generated wrapper type at compile time. The C# compiler wouldn’t let us (well, we could use dynamic, but then we’re giving up static typing). So we’ll be using an Unwrap method, giving us access to the bare T. (Note that we can’t use a property, since that would show up when auto-generating columns!)

Now how can we call Unwrap if the type doesn’t even exist at compile time? Well, we know that there’s a small set of core capabilities that all wrapper types are going to need: the wrapped instance of T, and a way of wrapping and unwrapping T. So let’s create an abstract base class containing just that:

abstract class Box<T>

{

protected T _;

public T Unwrap() { return _; }

public Box<T> Create(T t)

{

var box = MemberwiseClone();

box._ = t;

return box;

}

}

That way, we can always cast to Box<T>, call Unwrap, and we’re good.

Why are we calling it a “box”, by the way? It’s sort of a tip of the hat to academia, of all things. According to this paper on micro patterns, a “box” is “a class which has exactly one, mutable, instance field”. That suits our implementation to a T (hah!) so “box” it is.

The concrete box for our example should conceptually look like this:

public class BoxedICanine : Box<ICanine>, ICanine

{

public string Bark

{

get { return _.Bark; }

}

public bool Eats(Food f)

{

return _.Eats(f);

}

}

Of course, the boxes we generate at runtime will never actually have a C# manifestation - they will be bytecode only. At this point though, the hand-written example will prove useful as target for our dynamically generated type.

Note that we’re going to try to be a little clever in our implementation. In the case where T is an interface (like ICanine), we’re going to let the dynamically generated box implement the original interface T, in addition to extending Box<T>. This will allow us to pretend that the box isn’t even there during data binding. You might recall that we’re casting to ICanine rather than calling Unwrap in the FoodColumnTemplate, even though the data item is our dynamically generated type rather than the original canine. Obviously we won’t be able to pull off that trick when T is a class, since C# has single inheritance.

Looking at the bytecode for BoxedICanine in ILDASM, ILSpy or Reflector, you should see something like this (assuming you’re doing a release compilation):

.class public auto ansi beforefieldinit BoxedICanine

extends PolyFix.Lib.Box`1<class PolyFix.Lib.ICanine>

implements PolyFix.Lib.ICanine

{

.method public hidebysig specialname rtspecialname instance void .ctor() cil managed

{

.maxstack 8

L_0000: ldarg.0

L_0001: call instance void PolyFix.Lib.Box`1<class PolyFix.Lib.ICanine>::.ctor()

L_0006: ret

}

.method public hidebysig newslot virtual final instance bool Eats(valuetype PolyFix.Lib.Food f) cil managed

{

.maxstack 8

L_0000: ldarg.0

L_0001: ldfld !0 PolyFix.Lib.Box`1<class PolyFix.Lib.ICanine>::_

L_0006: ldarg.1

L_0007: callvirt instance bool PolyFix.Lib.ICanine::Eats(valuetype PolyFix.Lib.Food)

L_000c: ret

}

.method public hidebysig specialname newslot virtual final instance string get_Bark() cil managed

{

.maxstack 8

L_0000: ldarg.0

L_0001: ldfld !0 PolyFix.Lib.Box`1<class PolyFix.Lib.ICanine>::_

L_0006: callvirt instance string PolyFix.Lib.ICanine::get_Bark()

L_000b: ret

}

.property instance string Bark

{

.get instance string PolyFix.Lib.BoxedICanine::get_Bark()

}

}

This, then, is what we’re aiming for. If we can generate this type at runtime, using ICanine as input, we’re good.

If you’re new to IL, here’s a simple walk-through of the get_Bark method. IL is a stack-based language, meaning it uses a stack to transfer state between operations. In addition, state can be written to and read from local variables.

The .maxstack 8 instruction tells the runtime that a stack containing a eight elements will be sufficient for this method (in reality, the stack will never be more than a single element deep, so eight is strictly overkill). That’s sort of a preamble to the actual instructions, which come next. The ldarg.0 instruction loads argument 0 onto the stack, that is, the first parameter of the method. Now that’s confusing, since get_Bark seems to have no parameters, right? However, all instance methods receive a reference to this as an implicit 0th argument. So ldarg.0 loads the this reference onto the stack. This is necessary to read the _ instance field, which happens in the ldfld !0 instruction that follows. The ldfld !0 pops the this reference from the stack, and pushes the reference held by the 0th field (_) back on. So now we got an reference to an ICanine on there. The following callvirt instruction pops the ICanine reference from the stack and invokes get_Bark on it (passing the reference as the implicit 0th argument, of course). When the method returns, it will have pushed its return value onto the stack. So there will be a reference to a string there. Finally, ret returns from the method, leaving the string reference on the stack as the return value from the method.

If you take a look at the Eats method next, you’ll notice it’s practically identical to get_Bark. That’s because we’re essentially doing the same thing: delegating directly to the underlying T instance referenced by the _ field.

Now, how can we generate stuff like this on the fly?

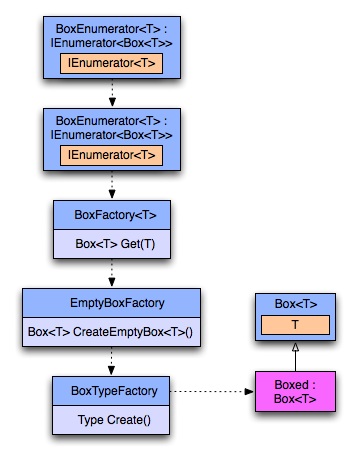

As you can see below, a .NET type lives inside a module that lives inside an assembly that lives inside an appdomain.

So before we can start generating the actual type, we need to provide the right environment for the type to live in. We only want to create this environment once, so we’ll do it inside the constructor of our singleton EmptyBoxFactory:

private readonly ModuleBuilder _moduleBuilder;

private EmptyBoxFactory()

{

const string ns = "PolyFix.Boxes";

_moduleBuilder = Thread.GetDomain()

.DefineDynamicAssembly(new AssemblyName(ns), AssemblyBuilderAccess.Run)

.DefineDynamicModule(ns);

}

AssemblyBuilderAccess.Run indicates that we’re creating a transient assembly - it won’t be persisted to disk. We’re holding on to the module builder, which we’ll use when creating types later on. Assuming that we’ll be using the BoxEnumerable<T> in multiple data binding scenarios (for various Ts), the module will be accumulating types over time.

The public API of EmptyBoxFactory is limited to a single method, CreateEmptyBox. It uses reflection to create an instance of the appropriate type.

public Box<T> CreateEmptyBox<T>()

{

return (Box<T>)Activator.CreateInstance(GetBoxType<T>());

}

Creating the instance is simple enough (albeit slower than newing up objects the conventional way). The real work lies in coming up with the type to instantiate, so we need to move on! GetBoxType<T> looks like this:

private Type GetBoxType<T>()

{

var t = typeof(T);

string typeName = t.FullName + "Box";

foreach (var existingType in _moduleBuilder.GetTypes())

{

if (existingType.FullName == typeName)

{

return existingType;

}

}

return CreateBoxType(t, typeof (Box<T>), typeName);

}

We’re still treading the waters, though. Specifically, we’re just checking if the module already contains the suitable box type - meaning that we’ve been down this road before. Assuming we haven’t (and we haven’t, have we?), we’ll go on to CreateBoxType. Hopefully we’ll see something interesting there.

public Type CreateBoxType(Type t, Type boxType, string typeName)

{

var boxBuilder = _moduleBuilder.DefineType(

typeName, TypeAttributes.Public, boxType, t.IsInterface ? new[] {t} : new Type[0]);

var f = boxType.GetField("_", BindingFlags.Instance | BindingFlags.NonPublic);

return new BoxTypeFactory(t, boxBuilder, f).Create();

}

Oh man, it seems we’re still procrastinating! We haven’t reached the bottom of the rabbit hole just yet. Now we’re preparing for the BoxTypeFactory to create the actual type.

Two things worth noting, though. One thing is that if t is an interface, then we’ll let our new type implement it as mentioned earlier. This will let us pretend that the box isn’t even there during data binding. The other thing is that we’re obtaining a FieldInfo instance to represent the _ field of BoxType<T>, which as you’ll recall holds the instance of T that we’ll be delegating all our method calls and property accesses to. Once we have the FieldInfo, we can actually forget all about BoxType<T>. It’s sort of baked into the TypeBuilder as the superclass of the type we’re creating, but apart from that, BoxTypeFactory is oblivious to it.

But now! Now there’s nowhere left to hide. Let’s take a deep breath, dive in and reflect:

class BoxTypeFactory

{

private readonly Type _type;

private readonly TypeBuilder _boxBuilder;

private readonly FieldInfo _field;

private readonly Dictionary<string, MethodBuilder> _specials = new Dictionary<string, MethodBuilder>();

public BoxTypeFactory(Type type, TypeBuilder boxBuilder, FieldInfo field)

{

_type = type;

_boxBuilder = boxBuilder;

_field = field;

}

public Type Create()

{

foreach (MethodInfo m in _type.GetMethods())

{

if (!IsGetType(m)) CreateProxyMethod(m);

}

foreach (PropertyInfo p in _type.GetProperties())

{

ConnectPropertyToAccessors(p);

}

return _boxBuilder.CreateType();

}

private static bool IsGetType(MethodInfo m)

{

return m.Name == "GetType" && m.GetParameters().Length == 0;

}

private void CreateProxyMethod(MethodInfo m)

{

var parameters = m.GetParameters();

// Create a builder for the current method.

var methodBuilder = _boxBuilder.DefineMethod(m.Name,

MethodAttributes.Public | MethodAttributes.Virtual,

m.ReturnType,

parameters.Select(p => p.ParameterType).ToArray());

var gen = methodBuilder.GetILGenerator();

// Emit opcodes for the method implementation.

// The method should just delegate to the T instance held by the _ field.

gen.Emit(OpCodes.Ldarg_0); // Load 'this' reference onto the stack.

gen.Emit(OpCodes.Ldfld, _field); // Load 'T' reference onto the stack (popping 'this').

for (int i = 1; i < parameters.Length + 1; i++)

{

gen.Emit(OpCodes.Ldarg, i); // Load any method parameters onto the stack.

}

gen.Emit(m.IsVirtual ? OpCodes.Callvirt : OpCodes.Call, m); // Call the method.

gen.Emit(OpCodes.Ret); // Return from method.

// Keep reference to "special" methods (for wiring up properties later).

if (m.IsSpecialName)

{

_specials[m.Name] = methodBuilder;

}

}

private void ConnectPropertyToAccessors(PropertyInfo p)

{

var paramTypes = p.GetIndexParameters().Select(ip => ip.ParameterType).ToArray();

var pb = _boxBuilder.DefineProperty(p.Name, p.Attributes, p.PropertyType, paramTypes);

WireUpIfExists("get_" + p.Name, pb.SetGetMethod);

WireUpIfExists("set_" + p.Name, pb.SetSetMethod);

}

private void WireUpIfExists(string accessor, Action<MethodBuilder> wireUp)

{

if (_specials.ContainsKey(accessor))

{

wireUp(_specials[accessor]);

}

}

}

Oh. That’s almost anti-climatic - it’s not really hard at all. The Create method is super-simple: create proxy methods for any public methods in the type we’re wrapping, wire up any properties to the corresponding getter and/or setter methods, and we’re done! CreateProxyMethod seems like it might warrant some explanation; however, all we’re really doing is copying verbatim the IL we looked at in our walkthrough of get_Bark earlier. The wiring up of properties is necessary because a property consists of two parts at the IL level, a .property thing and a .method thing for each accessor. That, too, we saw in the IL of the hand-written class. So there’s really not much to it.

You might note that we’re explicitly not creating a proxy for the GetType method, defined on System.Object. This applies to the case where the type we’re boxing is a class, not an interface. In general, we shouldn’t proxy any non-virtual methods inherited from System.Object, but in practice that’s just GetType. So we’re taking the easy way out. (Note that the .NET runtime wouldn’t actually be fooled if we did inject a lying GetType implementation - it would still reveal the actual type of the object. Still, it’s better to play by the book.)

We will be providing proxies for virtual methods, though (e.g. Equals, GetHashCode and ToString). This makes the box as invisible as possible.

There’s actually an alternative way of getting around the problem with broken polymorphism in simple scenarios. Rather than hand-writing your own wrapper or generating one at runtime, you can have the C# compiler generate one for you at compile time, using anonymous types. In fact, you can approximate a working solution for our example just by doing this in the code-behind:

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

_grid.DataSource = GetCanines().Select(

c => new {

Biscuit = c.Eats(Food.Biscuit),

Meatballs = c.Eats(Food.Meatballs),

You = c.Eats(Food.You),

c.Bark

});

_grid.DataBind();

}

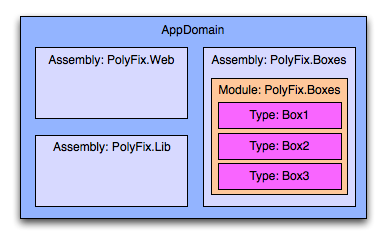

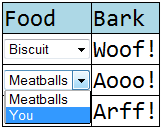

Note that you don’t add any custom columns in this case, it’s all auto-generated. Running the application, you get this:

It’s not exactly the same as before, but it’s pretty close. Unfortunately, the approach isn’t very flexible - it breaks down as soon as you want to display something that’s not just text in the grid. For instance, say you want something like this:

Anonymous types won’t help you, but the runtime wrapper will (as will a hand-written one, of course). You just need a suitable ITemplate:

public class FoodListColumnTemplate : ITemplate

{

public void InstantiateIn(Control container)

{

var list = new DropDownList();

list.DataBinding += OnDataBinding;

container.Controls.Add(list);

}

private void OnDataBinding(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

var list = (DropDownList) sender;

var row = (DataGridItem) list.NamingContainer;

var canine = (ICanine) row.DataItem;

Action<Food> add = food => { if (canine.Eats(food)) { list.Items.Add(food.ToString()); } };

add(Food.Biscuit);

add(Food.Meatballs);

add(Food.You);

}

}

Turns out that generating types at runtime is no big deal. It provides a flexible solution to the data binding problem, without the need for mindless hand-written wrappers.

As usual, let me know if you think there’s something wrong with the approach or the implementation. Also, I’d love to hear it if you have a different solution to the problem.