April 13, 2011

Disclaimer: copy code from this site at your own peril!

So yeah, I wanted to share this simple LRU cache I put together. LRU means “least-recently-used”. The idea is that you want to keep the hottest, most useful elements in the cache, so you evict elements that haven’t been used for a while. It’s a useful approximation of Belady’s algorithm (aka the clairvoyant algorithm) in many scenarios. Wikipedia has all the details.

Of course, my LRU implementation (written in C#) is extremely simple, naive even. For instance, it’s not self-pruning, meaning there’s no threading or callback magic going on to make sure that elements are evicted as soon as they expire. Rather, you check for expired elements when you interact with the cache. This incurs a little bit of overhead for each operation. Also, it means that if you don’t touch the cache, elements linger there forever. Another name for that would be “memory leak”, which sounds less impressive than “LRU cache”, but there you go. (We’re going off on a tangent here. Why would you create a cache that you never use? So let’s assume that you’re going to use it. “Useful” sort of implies “use”, indeed it should be “ful” of it.)

(The implementation isn’t synchronized either, which means you could wreak havoc if you have multiple threads accessing it simultaneously. But of course, you would be anyway. None of us can write correct multi-threaded code, so we should just refrain from doing so until the STM angel arrives to salvage us all. I believe his name is “Simon”.)

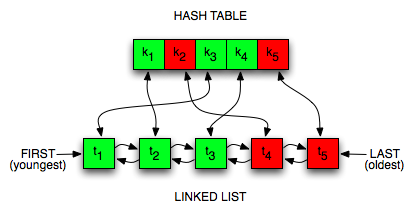

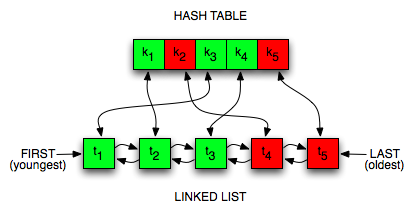

Anyways, the basic idea of an LRU cache is that you timestamp your cache elements, and use the timestamps to decide when to evict elements. To do so efficiently, you do two kinds of book-keeping: one for lookup, another for pruning of expired elements. In my implementation, this translates to a hash table and a linked list. The linked list is sorted by age, making it easy to find the oldest elements. New elements are added to the front, elements are pruned from the back. Pretty simple. I’ve sketched it below, just in case you cannot read.

The cache in the figure holds five elements, two of which have expired. To be extraordinarily pedagogical, I’ve colored those red. The still-fresh elements are green. Notice that there are arrows going both ways between the hash table and the list. We’ll be using both to do our double book-keeping.

Now, let’s look at the implementation details. Performance-wise, we want to keep everything nice and O(1), with the caveat that there’ll be a little book-keeping going on. It shouldn’t be too bad, there’s not much to do.

A skeletal view of the ExpirationCache class looks like this:

/// <summary>

/// Simple LRU cache with expiring elements.

/// </summary>

public class ExpirationCache<TKey, TValue> where TValue : class

{

private readonly Dictionary<TKey, LinkedListNode<KeyValuePair<TKey, TimeStamped<TValue>>>> _dict

= new Dictionary<TKey, LinkedListNode<KeyValuePair<TKey, TimeStamped<TValue>>>>();

private readonly LinkedList<KeyValuePair<TKey, TimeStamped<TValue>>> _list

= new LinkedList<KeyValuePair<TKey, TimeStamped<TValue>>>();

private readonly TimeSpan _lifetime;

...

}

There’s a fair amount of generic noise there, but the important stuff should be graspable. We can see the hash table (i.e. the Dictionary) and the linked list, as well as the TimeSpan which determines how long items should be held in the cache before expiring. The type declaration reveals that the cache holds elements of type TValue, that are accessed by keys of type TKey.

The TimeStamped type is simply a way of adding a timestamp to any ol’ type, like so:

struct TimeStamped<T>

{

private readonly T _value;

private readonly DateTime _timeStamp;

public TimeStamped(T value)

{

_value = value;

_timeStamp = DateTime.Now;

}

public T Value { get { return _value; } }

public DateTime TimeStamp { get { return _timeStamp; } }

}

Let’s look at something a bit more interesting: the pruning. (Of course, I don’t know if caches can really be “pruned”, as they’re not plants. But programming is the realm of mangled metaphors, so we’ll make do.) Here’s the Prune method:

private void Prune()

{

DateTime expirationTime = DateTime.Now - _lifetime;

while (true)

{

var node = _list.Last;

if (node == null || node.Value.Value.TimeStamp > expirationTime)

{

return;

}

_list.RemoveLast();

_dict.Remove(node.Value.Key);

}

}

The linked list is the tool we use for pruning. We iterate over the list backwards, starting with the last and oldest element. If the element has expired, we need to remove it from both the linked list and the dictionary. Of course, these operations must be O(1), or we’re toast. Removing the current node from a linked list is not a problem, but what about the dictionary? We need access to the key, so the linked list node needs to contain that. Once we have that, we’re good. We stop iterating once we reach an element that hasn’t expired yet. The neat thing is that we never look at more than a single non-expired element, since the list is sorted by age.

There are plenty of variations that you might consider. You might want to pose a strict limit on the number of elements, for instance. You might use that instead of, or in conjunction with, the expiration time.

How aggressively should we be pruning the cache? In my implementation, I prune on all operations, including counting elements in the cache. But you could choose different approaches. For instance, if you don’t mind serving slightly stale elements, you could prune only when adding. Speaking of adding: what happens when you add an element to the cache?

There are two scenarios to consider when adding an element to the cache: 1) adding a new element, and 2) replacing an existing element. Let’s look at the code to see how it’s done.

public void Add(TKey key, TValue value)

{

Prune();

if (_dict.ContainsKey(key))

{

_list.Remove(_dict[key]);

_dict.Remove(key);

}

var ts = new TimeStamped(value);

var kv = new KeyValuePair(key, ts);

var node = new LinkedListNode(ts);

_list.AddFirst(node);

_dict[key] = node;

}

After the mandatory pruning step is done, we can do what we’re here for. Let’s assume we’re adding a new element first. It’s trivial, even though we need to nest a few type envelopes: we’re wrapping our element in a TimeStamped inside a KeyValuePair inside a LinkedListNode. Then we just put that in front of the list (because it’s our newest one), and add it to the dictionary. Replacing an existing element is not much harder; we just remove it before adding it. We can’t mutate it, since we need a new timestamp and - more importantly - a new position in the linked list. We can’t afford to shuffle things around, since we’d lose O(1) in a heartbeat.

There isn’t much to it, really. Look up is a pure hash table operation:

public TValue Get(TKey key)

{

Prune();

return _dict.ContainsKey(key) ? _dict[key].Value.Value.Value : null;

}

Of course, you need open up all those type envelopes, too. But that’s pretty much it. For convenience, it’s nice to add an indexer, like so:

public TValue this[TKey key]

{

get { return Get(key); }

set { Add(key, value); }

}

And we’re done! If you think the implementation sucks or is flat-out broken, please tell me why.